European regulators have rejected a licence application for a new drug based on a human protein extracted from the milk of genetically altered goats. If the drug had been given the go-ahead by the European Medicines Agency (EMEA), it would have been the first treatment of its kind to be approved for clinical use. Atryn was developed by US firm GTC Biotherapeutics, for treating patients affected by a rare inherited blood clotting disorder. The company has said it will appeal against the decision, and also plans to apply to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for permission to sell the drug in the US next year.

Atryn contains the human version of antithrombin (AT), a blood protein that blocks the formation of clots. People born with congenital antithrombin deficiency have low levels of the protein, which can lead to an increased risk of abnormal blood clots forming - particularly in 'high-risk' situations, such as when patients are undergoing surgery. Infusions of Atryn would temporarily control the disorder, say its manufacturers, who had tested the drug on 14 patients. However, because of changes to the way it was administered after the trial had begun, the EMEA would only consider results from five of the participants - too few, it said, to determine whether Atryn was safe or not.

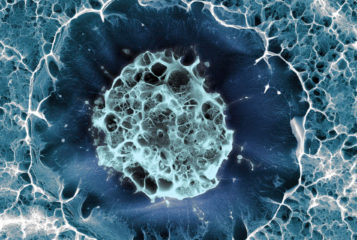

The protein is made by inserting the human AT gene into goat embryos, creating genetically altered animals that act as living drug factories. To ensure the drug is produced in the correct place, the AT gene is hooked up with the 'control switch' for casein, a protein exclusively present in milk. Several biotech companies are hoping to use this approach to produce large quantities of human proteins for treating a range of diseases. Another 'pharming' technique being used by some firms is to breed hens that produce human proteins in their eggs.

Therapeutic AT protein is currently obtained by purifying it from human blood. GTC has 57 goats that produce AT in their milk - potentially a much cheaper and efficient way of producing the drug, according to company director Geoffrey Cox. 'It takes just 18 months to produce a lactating animal and in a single year one goat produces the equivalent of 90,000 blood collections', he told the BBC News website. Another advantage of the approach is that it bypasses contamination concerns with products derived from human blood plasma products.

The EMEA acknowledges that the small number of patients treated so far is down to the fact that the disease only affects one person in 3-5000, but says it needs results from at least 12 people. It also says that the company didn't carry out enough studies to see if Atryn would trigger an immune response, a potential risk with any protein-based drug. The firm is now planning to test Atryn on a further 17 people for its US application. Despite the rejection in Europe, GTC's executives said they were encouraged that none of the EMEA's objections related to the way in which Atryn is produced. 'They identified concerns, and none of them relates to a goat', said spokesman Thomas Newberry.

Sources and References

-

Questions and answers on recommendation for refusal of marketing application for Atryn

-

Rejection of drug shows risks of biotech business

-

'Pharmed' goats seek drug licence

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.