Embryo freezing is generally seen as a routine part of IVF and ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) treatment. It offers many benefits, not least the fact that embryos left over from a fresh cycle can be stored for future use. This has implications for the patient's health and wellbeing - it avoids unnecessary gonadotrophin stimulation and repeated egg collections - and is less costly in the long run for the patient or NHS. Embryo transfer (ET) can be delayed when there is a risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome or the patient is unwell. Embryo storage is also the most reliable option for a woman with a partner who wishes to have children after sterilising cancer therapy. Facilitated by a reliable freezing programme, a move towards single ET would result in fewer multiple pregnancies.

Patients often ask about the risks associated with embryo freezing and the frequency of their questions increases after media reports which suggest that freezing may be unsafe. But how well founded are such reports: is freezing hazardous or are alarming reports just hype? The question 'Is embryo freezing safe?' begs several others, including 'What are the risks for the embryos?'; 'Will they still be able to develop normally?'; 'What are the risks for the woman?' But the question probably of most concern to patients is 'Are there risks for children conceived from frozen embryos?' or, put another way, 'Will they be normal?'

Embryos may be damaged by the processes of freezing and thawing or by technical or human error. Measures actively introduced by clinics, in conjunction with the HFEA's new adverse incident reporting scheme, minimise these latter risks. There is also a remote possibility of contamination with pathogens during storage in liquid nitrogen, although to the best of my knowledge this has never occurred during routine storage.

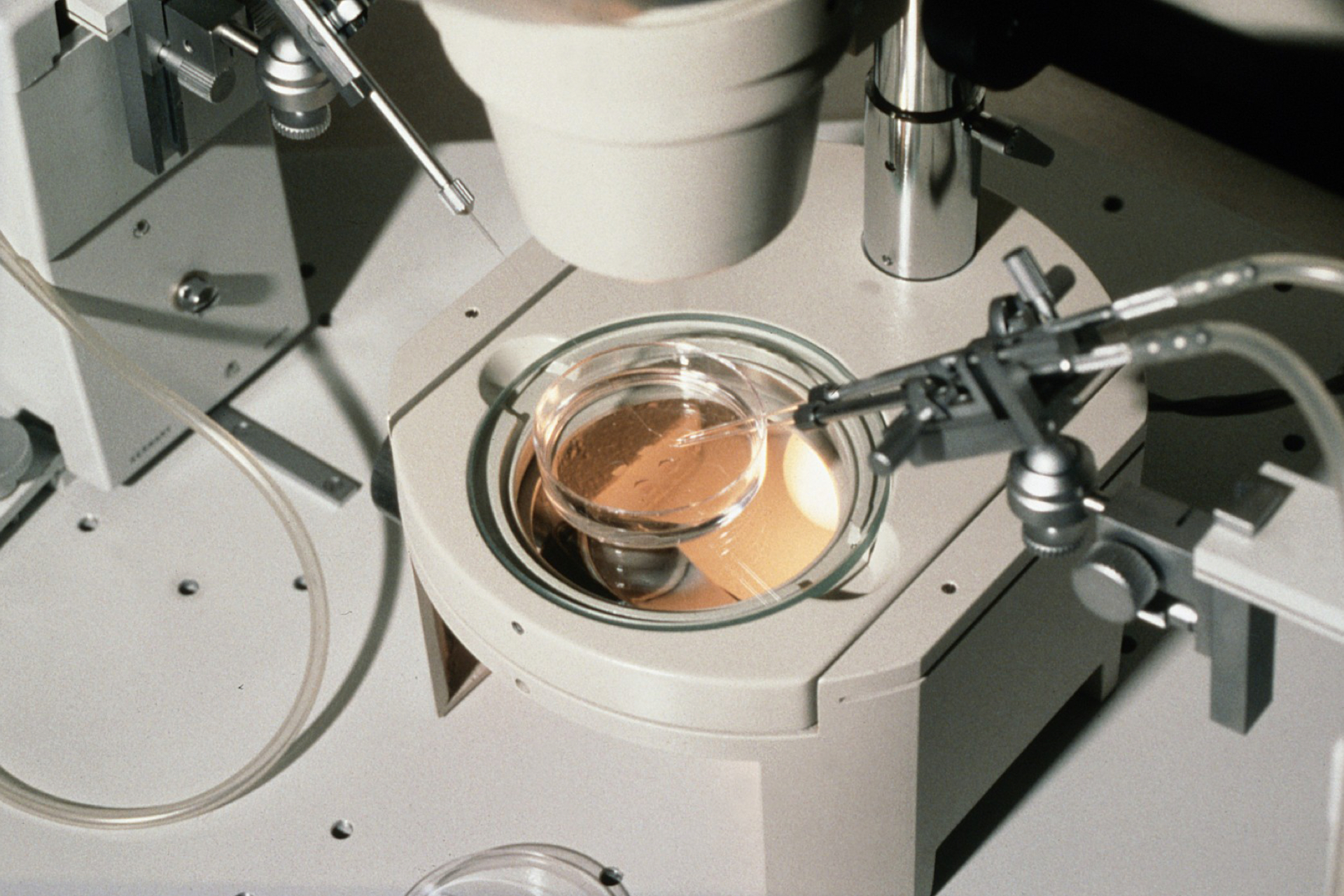

What are the risks from freezing and thawing per se? These can be measured in terms of embryo survival, viability after transfer, and whether freezing modifies gene expression or embryo phenotype. Cells of any kind, including embryos, endure a variety of insults during freezing. They are placed in solutions of potentially toxic cryoprotectants, before cooling to -196° C. Even under the strictly controlled conditions required for survival, the cells must withstand potentially lethal ice formation, transmembrane water movement and extreme changes in external electrolyte concentrations, temperature and pH. Thawing reverses these processes. After enduring such unphysiological conditions it is perhaps not surprising that some embryos fail to survive freezing. Survival varies from clinic to clinic: freezing is hazardous for some embryos (20-40 per cent don't survive) and some 'survivors' have one or more blastomeres damaged, but as many as 60 per cent of embryos may be completely intact after thawing.

Are these 'surviving' embryos viable? Can they implant and develop normally? HFEA data show that frozen ET's are significantly less likely to result in live births than fresh transfers. However, such data require further scrutiny since frozen ETs are rarely strictly comparable with fresh transfers. This is because the 'best' embryos are selected for fresh cycles and because embryos that have sustained some damage during freezing or thawing are often transferred. Additionally, more recipients of frozen embryos than fresh have previously had a failed transfer.

Several recent studies suggest that undamaged frozen-thawed embryos are as viable as their unfrozen counterparts. Damaged embryos can develop normally but their potential is reduced in vitro as well as in vivo. In one study, the rates of implantation and clinical pregnancy were significantly higher when intact embryos only were transferred, compared with transfers in which at least one embryo was damaged. In cycles where all embryos transferred were damaged, there was a significantly lower live birth rate and significantly fewer babies born per embryo transferred, compared with transfers of intact embryos. Comparing matched transfers of intact fresh and frozen embryos, the implantation rates were similar. In summary, some embryos simply don't survive freezing, others suffer damage that reduces their capacity for implantation, but about 50 per cent of embryos survive with all blastomeres intact and appear to have the same implantation potential as their unfrozen counterparts.

Do we have evidence that embryos are subtly changed by freezing? Reports of modified gene expression in frozen embryos raised concern. One study assessed levels of mRNA (messenger RNA) in the tuberous sclerosis gene, mutations of which result in the growth of benign tumours in various organs that may have severe consequences. mRNA levels were significantly lower in frozen-thawed than in fresh day two embryos. In embryos frozen on day three, the level of mRNA was similar to that in fresh embryos and, in embryos frozen on day two and then thawed and cultured for 24 hours to day three, the levels of mRNA were restored to normal day three levels.

What is the significance of these observations? They tell us that gene expression may be modified by freezing but we don't know whether there is any functional significance of this change. Is there a corresponding change in the protein encoded by the gene? Any change in cellular function? Or any long term effects? Animal studies suggest embryos are able to withstand quite extreme changes in gene expression. Other studies comparing the phenotype of frozen and thawed mouse embryos, e.g. distribution of cell surface antigens, have shown that although changes may be seen after freezing, normal developmental patterns are usually restored later. Whilst we can't ignore reports of modified gene expression, we need more extensive studies to allow considered judgement of their significance.

What of the risk to mothers? Generally, the incidence of risk to mothers after frozen ET is reported as similar to that after fresh transfer. Last year patients were alarmed by an American report showing a 17-fold increase in the risk of ectopic pregnancy after frozen ET in a sample of only 19 pregnancies. Data from clinics in Manchester and Aberdeen are reassuring, showing similar incidence of ectopics occurring after fresh and frozen ET in large groups of patients.

Patients are most concerned that freezing should carry no risk to any children conceived. Encouragingly, the incidence of pre-term birth, low birth weight and perinatal mortality is similar to that seen after fresh ET. The follow-up of birth defects, development and long-term health is more problematic. Several groups have reported on the occurrence of birth defects. All suggest that the incidence in frozen embryo conceptions is no different from that in fresh IVF or ICSI, but the evidence is inconclusive. Sample size is the major problem - when an anomaly has a low incidence in the general population then very large samples are required to show any significant increase after an intervention. We have simply not had follow-up studies of a sufficient number of children to be certain that there are no increased risks after freezing.

A few small studies have followed-up the development of children conceived from frozen embryos. They show no evidence of variation in several categories including growth, psychomotor development, health, intelligence or scholastic achievement. However, the authors point out that the samples are small and there are methodological difficulties: the question of how far follow-up can intrude into the lives of children is a major issue for researchers.

There is no evidence from human studies for the long-term safety of embryo freezing because the oldest children conceived from frozen embryos are barely 20 years old. Animal studies are generally encouraging: frozen embryos are used widely in commercial cattle breeding without evidence of increased abnormalities. In mice, no increase in mutation rate was seen after frozen embryo transfer and the offspring developed and reproduced normally. One long-term study did cause some alarm: while no major anomalies were found in mice conceived from frozen embryos, some more subtle changes were observed: e.g. in adult male body weight in one of two strains, but not in females; in some aspects of early development e.g. late eruption of incisor teeth but only in the strain of mice that developed more slowly; in learning, including avoidance conditioning; and in the size and shape of some bones in the mandible. These findings are difficult to interpret and continue to engage scientists in debate, particularly as most parameters of development showed no variation with freezing. Importantly, the study has never been repeated - perhaps it should be!In conclusion, many embryos that would otherwise be discarded soon after fertilisation, retain full viability after freezing, but some embryos don't survive and others have their developmental potential reduced. Otherwise there is no sound evidence that embryo freezing is hazardous. However, reports of modified gene expression in thawed embryos and minor phenotypic changes in animals conceived from frozen embryos cannot be ignored, and well designed experiments to pursue these possibilities are needed. Meanwhile, the benefits of embryo freezing appear to outweigh any potential risks. My fear is that if patients become alarmed by unfounded reports of the risks of freezing based on inadequate evidence, they will be deterred from accepting the transfer of just one embryo at a time which, by reducing the incidence of multiple births, is the best route to minimising the risks to mothers and children conceived by ET, and increasing the number of healthy babies born.

Maureen Wood is a research embryologist in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Aberdeen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.