Australia is on the cusp of legalising mitochondrial donation. Following a series of public consultations – the most recent of which proposed an Australian model for mitochondrial donation – a bill for the necessary law reform has passed two readings in parliament, and will go to a conscience vote in the next few months.

This bill is the culmination of several years of debate about whether the procedure should be permitted. However, the need for discussion is not over. Australia now needs to consider how mitochondrial donation might best be implemented.

The proposed Australian model resembles the dual licensing system in the UK (the first country to legalise mitochondrial donation). In Australia, just one clinic will be licensed to offer mitochondrial donation during the first phase of the model (which is expected to last 10-12 years.) Each patient seeking to use the service will also need separate approval, with similar eligibility requirements to the UK.

Some of the finer aspects of the Australian model remain vague, while others differ from the UK model for mitochondrial donation. Here, we describe three key questions that Australia will need to resolve in its legislation if it chooses to offer mitochondrial donation clinically.

Should mitochondrial donors be anonymous?

In both Australia and the UK, children who are born following IVF with donated gametes have a legal right to obtain identifying information about their donors upon majority. The Australian proposal would extend this right to children born of mitochondrial donation. This differs from the UK, where mitochondrial donors can remain anonymous.

Why did the UK allow donor anonymity? One argument is that mitochondrial donors make only a small genetic contribution to the resulting child – so the identity of mitochondrial donors should matter less to children than the identity of standard egg donors.

However, while mitochondrial donors contribute less DNA than a standard egg donor, to focus on the amount of genetic material fails to acknowledge the significant contribution of mitochondrial donors to the birth of healthy children, who might otherwise have developed serious mitochondrial disease. And for women who donate, the donation process is the same.

Mitochondrial donation, then, resembles standard egg donation in important respects. While Australia's approach to donor anonymity differs from that of the UK, we believe this difference is a strength of the Australian model.

Should sex selection be permitted?

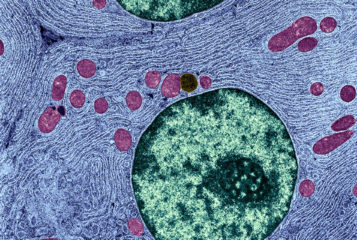

Mitochondrial DNA is inherited maternally from the mitochondria in the ovum. This means girls born using mitochondrial donation would therefore pass their donated mitochondria to their own children, making the genetic change heritable. Boys, however, almost certainly would not.

The US Institute of Medicine has argued that only male embryos should be used in mitochondrial donation (at least initially), which would prevent changes to the human germline being passed to future generations. The UK, however, rejected this approach.

The Australian Government has proposed a third option: let parents decide whether to select a male embryo or proceed without sex selection. (This would require Australia to revise its regulation of sex selection, which is currently permitted only for limited medical reasons.)

This middle-ground proposal fails to fully resolve ethical concerns about either sex selection (controversial in Australia) or heritable germline changes (if daughters are born). It also has technical limitations: sex selection requires additional pre-implantation embryo testing, reducing cycle success rates. Further, although parents will receive at least some pre-treatment counselling, they may not be well-positioned to wade through the scientific and ethical complexities of this decision. Rather than providing the best of both worlds, the proposed compromise risks pleasing nobody. The issue of sex selection should be revisited.

How should donor eggs be sourced?

Mitochondrial donation involves gametes from three individuals: sperm from the prospective father (or sperm donor), an egg from the prospective mother, and an egg from a third party with healthy mitochondrial DNA. Where should these eggs be sourced from, given that Australia already has a shortage of donor eggs?

Eggs could theoretically be taken from the existing pool of eggs donated for use in assisted reproduction. However, there are ethical difficulties here. Current egg donors would probably not have anticipated that their eggs would be used for mitochondrial donation. They certainly have not specifically consented to this use.

Eggs could instead be sourced from donors who have consented specifically to their use in mitochondrial donation, under a system that would need to be set up soon. This might limit the availability of eggs for mitochondrial donation, at least initially. However, it would ensure eggs are not used without donors' informed consent. This trade-off is arguably well worth making.

The forthcoming conscience vote on mitochondrial donation is an important moment for Australia. However, even if the bill passes, important legal and ethical questions will remain – including, but not limited to, the three described above. These issues need careful attention if Australia is to set up an ethical system of mitochondrial donation.

With contributions from:

Dr Liz Sutton and Professor Catherine Mills from Monash Bioethics Centre, School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies, Monash University, Clayton, Australia

Esther Lestrell and Associate Professor Karinne Ludlow from Faculty of Law, Monash University, Clayton, Australia

Dr Chris Degeling from Australian Centre for Health Engagement, Evidence and Values, University of Wollongong

Professor Ainsley Newson from Sydney Health Ethics, Faculty of Medicine & Health, The University of Sydney, Australia

Professor Robert Sparrow from Philosophy, School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies, Monash University, Clayton, Australia

Dr Narelle Warren from School of Social Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Australia

Sources and References

-

Mitochondrial donation in Australia

-

Mitochondrial donation law reform (Maeve’s Law) bill 2021

-

Coalition allows free vote on disease fix

-

UK becomes first country to give go ahead to three-parent babies

-

Mitochondrial donation treatment

-

Explanatory memorandum to the human fertilisation and embryology (mitochondrial donation) regulations 2015

-

Mitochondrial replacement techniques: ethical, social, and policy considerations

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.