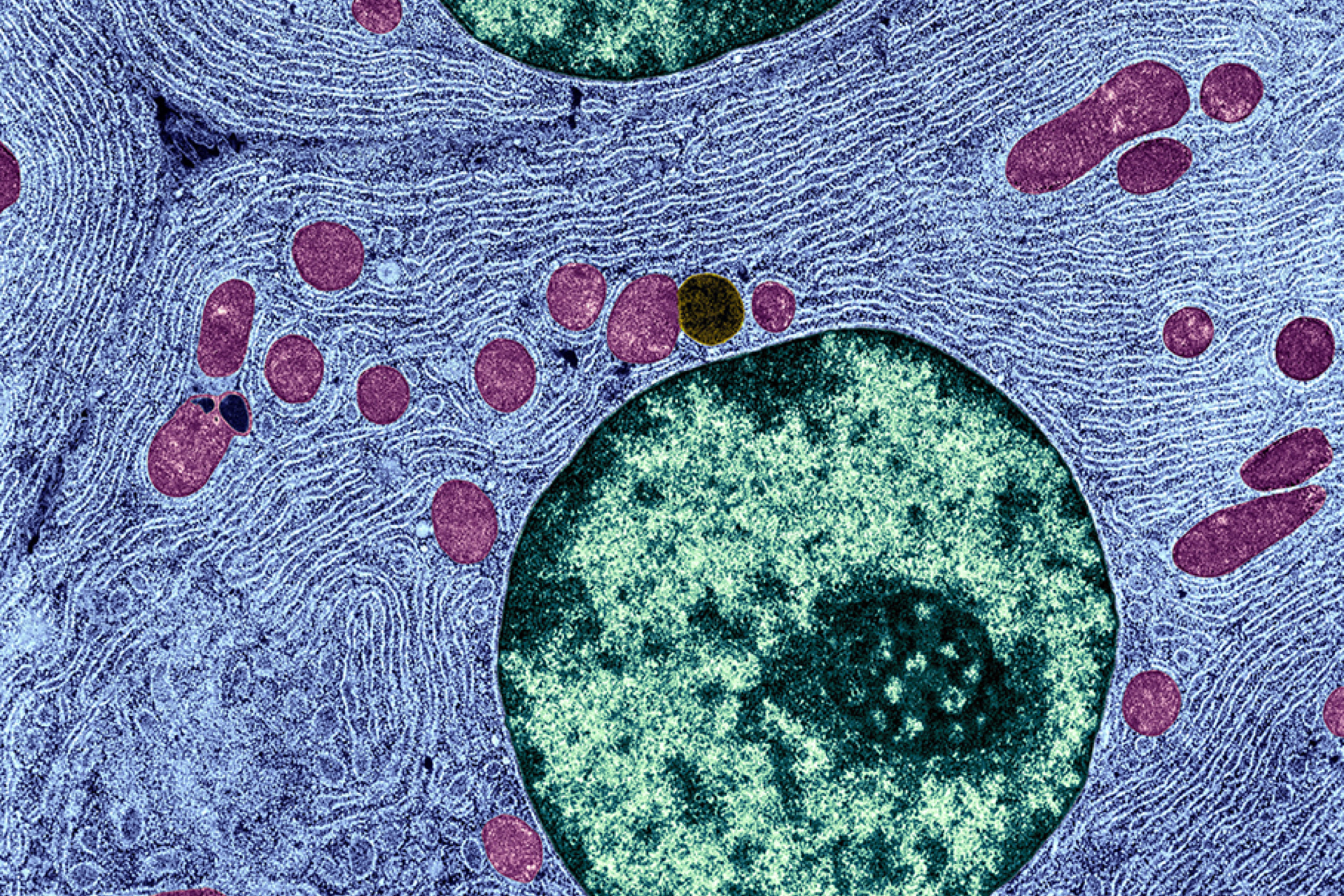

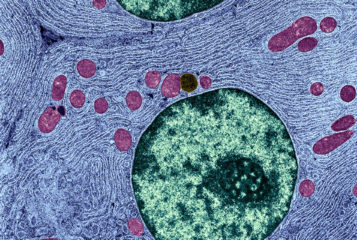

Mitochondrial donation has seeded a growing literature in bioethics, law and the social sciences. This technology, which introduces third-party mitochondria to an embryo or oocyte, has contributed to many long-standing social and ethical questions. Should we allow inheritable changes to the genome? Should we value genetic relatedness? How should we balance wants and needs when it comes to novel reproductive technologies? Will couples feel pressured to use it? How can regulation keep up with fast-moving science?

A committee of the Australian Senate has recently endorsed mitochondrial donation for couples at risk of passing on mitochondrial disease (see BioNews 956). It is worth noting that the term 'mitochondrial donation' is imperfect. However, it was the term used in the Australian inquiry. I have also used this term in my own publications.

The 114-page Senate committee report is the result of a three-month inquiry, during which the committee gathered evidence, including soliciting submissions and staging a public hearing. The report provides qualified support for changing Australian laws to allow clinical use of mitochondrial donation, subject to further public consultation.

It also refers three questions to the National Health and Medical Research Council:

- Are mitochondrial donation and germline genetic modification distinct?

- Are there any new scientific findings since the legalisation of this technology in the UK that might prevent its introduction in Australia?

- Are there any methods besides mitochondrial donation that should be investigated?

The report also recommends the Government explore whether Australians could be given help to access mitochondrial donation in the UK. This appears to be an instance of a government endorsing reproductive tourism – an unusual move. I would suggest that this has been included to offer an immediate option for at-risk Australian couples, but also to mitigate the chance of Australians seeking mitochondrial donation in less regulated jurisdictions.

In my view, the committee has done an admirable job of weighing the many issues and competing positions that were put to it during its consultation. The report is nicely nuanced and shows that the evidence it received was carefully considered, but not always agreed with. The hope of mitochondrial donation for families living with mitochondrial disease is recognised, without over-hyping it as a cure. The report also rejects the misleading 'three-parent' label, which conflates genetic and social parenting.

The report looks to the UK's experience, particularly with regard to safety. But there are also departures from the UK's precedent. For example, despite also using an analogy between mitochondrial donation and organ donation, the report states that oocyte donation should be identifiable, as per other kinds of reproductive donation. The report supports a child's right to know their biological heritage. In the UK, regulations prohibit the release of identifying information to children born following mitochondrial donation. The only permitted way to release identifying information is if the donor chooses to waive their anonymity.

I was among those contributing evidence for the committee to consider. My submission advocated against anonymous donation on the grounds that the analogy with organ donation was problematic. The donation makes a small but fundamental contribution for any child born, and anonymity risks underplaying the role of the woman who donates her oocyte. As such, I concur with the position taken.

The Senate also claims that manipulating the mitochondrial DNA complement in a cell is different to changing nuclear DNA. This is one reason why mitochondrial donation may not be the same as other forms of germline intervention – a question I have previously considered with Dr Anthony Wrigley. In our view, mitochondria have 'conditional inheritance'. This is because they are inherited through the maternal line, because of their high rate of mutation and because of their random distribution during cell division, among other properties.

Mitochondrial donation is thus conceptually distinct from other germline genetic modifications. We concluded that its automatic prohibition on this ground alone would therefore be inappropriate.

The report did not devote much space to what many consider to be one of the most significant ethical issues in mitochondrial donation: the perceived and normative value of genetic relatedness (see BioNews 949). In my submission, I advocated for the committee to recognise this debate, including that this value is widely assumed to be held, but rarely considered carefully in its own right.

I suggested that couples seeking mitochondrial donation should explore the values underlying their preference for genetic relatedness as part of their counselling. It was disappointing to see that the report skated over this issue, saying little more than genetic relatedness was valued by couples.

The report also didn't mention the possibility of using mitochondrial donation to allow a genetic connection between lesbian parents and their child. This has been recently debated in the Journal of Medical Ethics here and here. My submission suggested that at this early stage, limiting the use of mitochondrial donation would be prudent. At present, it seems clear that the Australian intention is to regulate for the use of mitochondrial donation to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial disease only.

The use of mitochondrial donation by lesbian partners requires further ethical discussion on the preference for genetic relatedness. We need to debate questions like, should the quantity of the genetic link make a moral difference? How should this preference be weighed against an invasive and inheritable genome modification?

The report appears to ringfence the creation of human embryos for the purposes of mitochondrial donation as a 'new moral question'. It does not explain why this is different. It also hints that there may be other methods that should be explored (as mentioned above) but does not elaborate on what these might be. This new moral question is delegated to the National Health and Medical Research Council for further consideration.

The Australian Senate's report shows that the journey to legalisation is likely to be slow. As Dr Karinne Ludlow has recently discussed, Australia has a splintered regulatory regime when it comes to assisted reproduction. There are multiple pieces of legislation at state and federal levels that will need to be amended to make clinical use of mitochondrial donation a reality, Dr Ludlow notes. This is before any licensing regime kicks in.

But the complexities thrown up by Australia's regulatory regime will also generate space for further public debate on how Australia should provide this technology to the couples who seek to use it. Australia should seek to avoid some of the perceived problems in the UK, including claims that mitochondrial donation was oversimplified and that key points, such as its inheritability and the role of mitochondrial DNA, have been underplayed in the run-up to passing the legislation.

As an emerging technology, mitochondrial donation is an intervention with inherent degree of uncertainty. This needs to be accounted for and built in to regulation and eventual clinical provision. This will ensure mitochondrial donation is eventually provided in a way that appropriately balances the interests of those families who seek to use it with the wider ethical and social issues.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.