To those who followed the story of Diane Blood in the '90s, the plight of the woman referred to as 'L' in recent news articles has a strong sense of deja vu (1). Once again, sperm has been obtained from the body of a man without his prior consent. Once again, the widow seeks to use the sperm to conceive a child, and has been embroiled in a legal battle to be allowed to do so. But how could such an agonising situation occur twice? Surely if nothing else, Diane Blood's case ought to have clarified the legal landscape here, meaning that in future such tortuous legal wranglings could be avoided? Unfortunately, it seems not.

When sperm was removed from the body of Diane Blood's dying husband, the law had yet to be tested on the question of whether this was acceptable. A report was commissioned, with the aim of clarifying the law. Authored by Professor Sheila McLean of Glasgow University, this was published in 1998. A summary of its findings can be found on the Department of Health's website, including the following stipulations from the then Minister for Public Health:

- 'In terms of the common law provisions relating to the removal of human gametes, the report recommends that the current requirement for formal consent following adequate disclosure of information, should remain;

- The courts should be asked to determine whether the removal of gametes is lawful where there is any doubt about such removal in cases where consent cannot be given in the usual way;

- The requirement of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 for consent to certain treatment provided under the Act (such as IVF and donor insemination) to be given in writing should remain, and be extended to all treatment provided under the Act;

- That the 1990 Act should be amended to remove from the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority any discretion to permit the export of human gametes that have been removed unlawfully' (2).

According to this report, the removal of gametes without consent may indeed contravene the law. But the problem that remains in these circumstances is the question of what to do with gametes that have already been obtained without consent. From Mrs Blood's perspective the answer to this must have seemed self-evident. There was nothing to be gained by destroying the sperm. Her husband was dead and could not be benefited in any way. The lengthy court battles would all have been for nought if it were ultimately decreed that the sperm must be destroyed.

However, this is where interpretations of the case differ. And it is clear that the Blood case has cast a long shadow. The HFEA sought to prevent Mrs Blood's use of the sperm precisely in order that a precedent should not be set (3,4). The HFEA, as everyone knows, and as Mrs Blood has cause to celebrate, was effectively overruled on this, and a precedent was set. Laws governing the export of goods for use in Europe were cited in order to force theHFEA to withdraw its refusal to permit Mrs Blood to take her husband's sperm abroad. Two facts thus emerged from Mrs Blood's legal battle. First, obtaining sperm from a dead or dying man who has not given prior consent is of questionable legality. Second, even if sperm has been obtained without consent, it may be taken abroad and used nevertheless. This second fact constitutes a powerful incentive for disregarding the first.

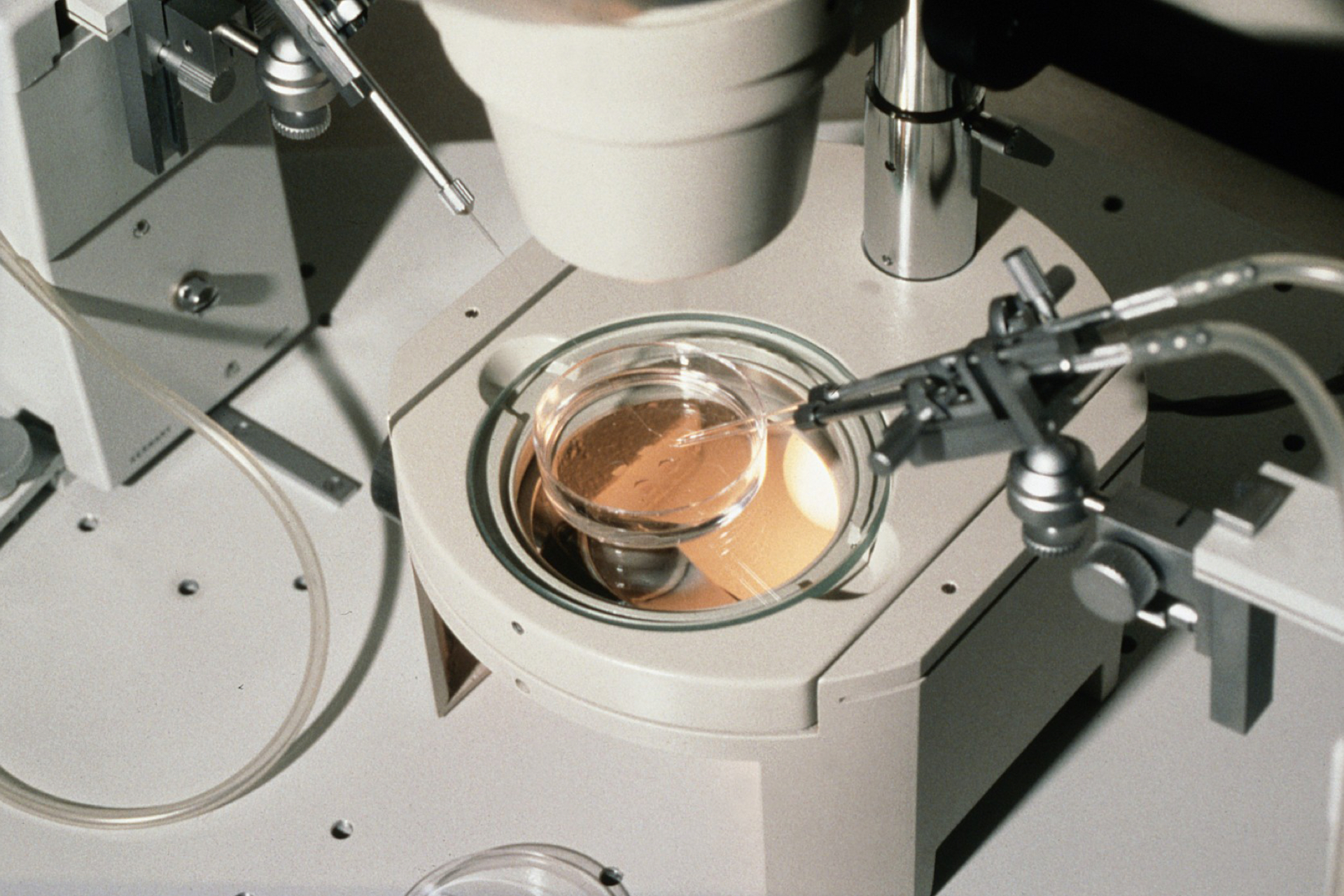

Those who obtained and subsequently stored sperm from L's husband obtained a court order before doing so. But the judge found that the court order exceeded its remit. It did not have the jurisdiction to authorise storage of sperm, and the validity of its authorisation of the sperm extraction can also be called into question (5). The case of 'L' demonstrates that despite the recommendations of Professor McLean's report, patients' bodies are still being subjected to sperm extraction. The word 'subjected' may seem excessive here, but few people, perhaps, are aware of the way in which sperm is obtained from incapacitated, dead or dying patients. An electric probe is inserted into the patient's rectum. Electric shocks are administered rhythmically, increasing in strength until ejaculation occurs. This usually results in sperm being discharged into the patient's bladder, where it is collected via a catheter (6).

It would be nicer not to think about the details of the procedure. But it is important to be clear about what exactly is being carried out, since this has a bearing on the issue. In her book, Mrs Blood mentions that she and her husband had discussed the posthumous use of sperm, and that he would have wished her to have his child after his death (7). But if a person does not know what the procedure entails, a willingness to have a posthumous child cannot be interpreted to entail willingness to undergo electroejaculation.

The bodies of dead and dying individuals are vulnerable to asault and exploitation, and the law's function is to protect them. This is precisely why consent is deemed to be so important in this context. But the precedent set in the Blood case has shown that the law may be powerless to prevent the use of tissues which have been obtained without prior consent. Had theHFEA won the Diane Blood case, it is highly improbable that this second case would have arisen. 'L' and her advisors would have had no incentive for extracting the sperm, since they would not have expected to be able to use it.

There are two possible ways of addressing this. Firstly, we could decide that dead and dying patients do not after all require such legal protection. The current requirements for consent could be jettisoned, so that people who wish to use the tissue of dead or dying patients could do so without having to go through the courts. Alternatively, we could bolster the laws that govern this area, by preventing people from using or exporting tissue obtained without consent. The judgments that have been passed so far seem to support the latter choice. But L may still appeal the ruling. Should she ultimately win the right to export the sperm, the recommendations of the McLean report will be further undermined.

Sources and References

-

3) Deech R, Smajdor A. From IVF to Immortality: controversy in the era of reproductive technology. Oxford University Press. 2007.

-

4) R v Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, ex parte Blood (1997)

-

6) Ohl DA, Sonksen J et al. Electroejaculation.

-

7) Blood D. Flesh and Blood: the human story behind the headlines. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. 2004.

-

1) Fight to use dead husband's sperm.

-

5) A note on L v. (1) HFEA and (2) Department of Health

-

2) Use Of Gametes: Report Published Following Review Of Procedures - Â Department of Health

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.