I was sitting down, reading an ethics article on how mitochondrial replacement techniques should be classified, when BioNews alerted me that New Scientist had announced the birth of the first baby using the very technology I was reading about. This baby had been born following maternal spindle transfer, one of the mitochondrial replacement techniques whose use was recently been made legal in the UK, and that is being discussed in the USA.

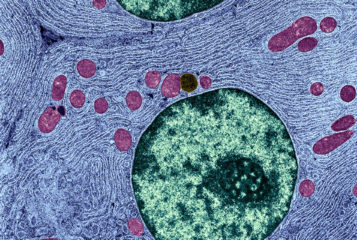

These techniques, in short, have been developed to allow women who carry mitochondrial DNA diseases – which can be debilitating and life-threatening – to avoid passing these on to their children. There are two main techniques for doing this. One of them rehouses the nuclear material from the intending mother's egg in the enucleated egg of a healthy donor; it is called maternal spindle transfer. The other one rehouses the nuclear material of a one-cell embryo produced with the intending parent's gametes; this is called pronuclear transfer.

Now, not has only Dr John Zhang's team announced the live birth of a baby, but that baby – who is five months old – is reportedly doing well (see BioNews 871). This is a remarkable biotechnological achievement. A happy event, I thought.

Then I stopped and wondered – where did this take place? And I read that it had all happened in Mexico. The horror! I kept on reading, and then things went from bad to worse – Zhang is on record saying that he and his team chose to work in Mexico because 'there are no rules' in Mexico. At that point, I wanted to shut down my computer and call it a day. I'd like to think Zhang is being quoted out of context, but the damage is done.

At this point you might think that I am a bio-conservative and that I oppose these techniques for ethical or religious reasons. On the contrary, I have been working on the ethics of mitochondrial replacement techniques for a while, and I am on record defending their moral acceptability. I think that, in principle, it is ethically acceptable to carry out both maternal spindle transfer and pronuclear transfer. In fact, I think the baby born in this instance has not been harmed by the technique (as in, made worse off) in any way, since if the technique hadn't been used he wouldn't have existed. I also think that women with mitochondrial DNA diseases should have access to these techniques if they wish to have genetically related children. Why, then, am I – someone born and raised in Mexico – putting such a downer on what should be seen as a good news story?

In Mexico, there are no federal laws governing assisted reproduction, although various proposed amendments to the National Health Law regarding assisted reproduction are currently being discussed by the Mexican Government. The amendment that seems to have the best chance of being passed into law is very conservative, and will restrict assisted reproduction in many ways.

Here is a taster of the proposed changes. No access to assisted reproduction for single people, unmarried couples or same-sex couples (this is particularly important, given that the president has recently proposed an amendment to the constitution in order to include a same-sex marriage provision). International surrogacy will be forbidden. National surrogacy may be allowed, but only if the gestating mother is filially related to the couple that provides the embryo.

Finally – and most importantly, for what we are discussing – the amendment will also impact upon mitochondrial replacement techniques, since it will specifically forbid the creation of genetically modified embryos. One can argue that in a strict sense, mitochondrial replacement techniques do not modify genes, and thus this provision will not apply. Even so, I think that such techniques are highly likely to be construed as causing genetic modifications.

Another section in the proposed amendment specifies that any kind of eugenic practice is forbidden. If the intention behind using mitochondrial replacement techniques is to have children without mitochondrial DNA diseases, then this fact will be used to label these practices as 'eugenic' because they prevent people with certain diseases from being brought into existence.

So I was horrified to read that the first place in the world where mitochondrial replacement techniques took place was in Mexico, because I believe this will ease the way for this very restrictive amendment to be made into law. Once passed, it is going to be an uphill battle to undo.

Why do I think this news will impact on changes to the law in Mexico? First, because the conservative sector will mobilise its political forces in order to stop more 'three-person babies' being created and born in Mexico, just as it has mobilised against same-sex marriage. Let's remember that the Catholic Church is still a major political player in Mexico.

Second, because this whole issue is going to be construed as American scientists taking advantage of our legal voids in order to carry out research that is not allowed in their country. This is not going to play well with Mexican politicians. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Sylvana Beltrones, the politician who proposed the amendment that has the greatest chance of being passed into law, yesterday told BBC Mundo that she and her colleagues are trying to forbid the techniques that allow for 'three-parent embryos' to be created.

Zhang's team opened a new door in terms of reproductive possibilities, but they may very well be instrumental in closing the assisted reproductive door for many people in Mexico. I really wish that Zhang and his team had thought this one through.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.