A revolutionary vaccine uses the patient's own immune response to target tumour cells and could be the first step in bespoke, precision medicine.

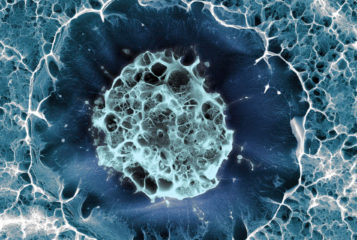

Researchers in two separate studies, both published in Nature, have targeted newly found proteins on the surface of tumour cells which are not present in healthy tissue. These 'neo-antigens' normally arise from genetic mutation within the tumour cells which means to they are unique only to those cells.

A sample is taken from each individual patient and sequenced to determine exactly which genetic mutations are present and hence what mutated proteins. Researchers then use software to predict which proteins are more likely to give a strong immune response.

'What's really exciting about this approach is that it involves sequencing their tumour and making a bespoke, customised vaccine,' says Professor Kevin Harrington of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, who was not involved in the research. 'When we have previously given vaccines, we have taken a generic approach and it was a bit hit-and-miss.'

Dr Catherine Wu from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston injected a combination of up to 20 of these mutated neo-antigens into the skin of six patients with melanoma who were deemed at a high risk of cancer recurrence. Of the six, four showed no recurrences of tumour growth after two years.

Instead of injecting proteins to elicit an immune response, researchers lead by Professor Ugur Sahin at German firm BioNTech, injected RNA encoding up to 10 mutated proteins into 13 patients. Cells use RNA as a template to make proteins, in this case the selected mutated proteins. Both techniques yielded similar results with eight out the thirteen patients injected having no cancer recurrence.

In addition in both studies 'a plan B' was also adopted where individuals whose cancer has developed further despite treatment were given a checkpoint inhibitor called PD-1 which blocks tumours from evading immune system attacks. This was shown to completely wipe out the tumour.

The difficulty facing cancer researchers has long been how to kill tumour cells whilst also sparing healthy tissue. Conventional therapies such as chemotherapy which target rapidly dividing cells are toxic to many healthy cell types and can have significant side effects.

In this new approach, the immune system – in particular the T (white blood) cells– become sensitised to the tumour-specific proteins and only attack cancer cells, leaving healthy cells untouched.

Although this method might work with any kind of cancer, skin tumours may be more vulnerable to immune attack. 'You could in theory vaccinate any tumour type,' Harrington says, 'but some will be more amenable to this sort of approach than others.'

Aside from the need for larger trials, one current hurdle is that the vaccines take around three months to produce which for some cancers may be too late.

Sources and References

-

Personalized cancer vaccines show glimmers of success

-

An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma

-

Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer

-

Cancer vaccines could prime our own bodies to fight tumours

-

Precision T-cell therapy targets tumours

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.