A baby has been born in the Ukraine following the use of an experimental IVF procedure known as mitochondrial donation.

Dr Valery Zukin, director of the Nadiya Clinic for Reproductive Medicine in Kiev, announced two pregnancies in October last year following use of a mitochondrial technique called pronuclear transfer that had been performed at the clinic (see BioNews 873), and which led to the birth of a baby girl on 5 January.

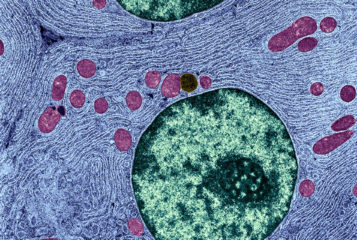

The technique involves fertilising two eggs – one from the mother and one from a donor – with the father's sperm and transferring the nuclear material from the mother's embryo to the donor's embryo. The newly created embryo gets its nuclear DNA from its mother and father, but its mitochondrial DNA is inherited from the donor.

News of the birth has attracted attention for the creation of a child with genetic material from three people – the mother, father and the donor – but also because it was employed as a means to address difficulties in conceiving, rather than preventing the transmission of mitochondrial disease, which can be potentially fatal.

While mitochondrial donation, including the technique used in the Ukraine, is permitted in the UK under a licence granted by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), it is only allowed if the patient is at risk of passing on a serious mitochondrial disease (see BioNews 826). However, in this case, Dr Zukin explained that the child's mother was affected by unexplained fertility and the technique was used as a means to prevent embryo arrest.

Speaking on the BBC World Service's Newshour, Sandy Starr of the Progress Educational Trust, which publishes BioNews, said there was no clear evidence that such a technique would work in these circumstances.

'There's little evidence that this technique will work to address embryo arrest. Mitochondrial donation involves risks which have been thoroughly assessed in the UK, but have only been assessed in relation to patients trying to avoid the transmission of mitochondrial disease, and it's on that basis that people have decided that in very specific circumstances and a regulated environment the risk is worth taking.

'Whether the risk is worth taking in relation to an experimental fertility treatment technique is as yet unexplored', he said.

While the UK is the first country to legislate to allow mitochondrial donation, the HFEA has not yet granted a licence to perform the technique in patients, although it is expected that the first procedures may be carried out in the UK later this year (see BioNews 880). The HFEA has conducted a series of reviews examining the safety and efficacy of mitochondrial donation, the last of which was in December when it approved its 'cautious clinical use' in the UK (see BioNews 882).

However, there remain concerns regarding the future inheritance of the donated mitochondria. Lori Knowles, assistant professor at the University of Alberta School of Public Health in Canada, told CNN News that the fact the child born in the Ukraine is a girl raises the concern that the donated mitochondria can be passed on to future generations.

'I do think it's highly significant that this is a girl because we know for sure that she will be passing on her mitochondrial DNA through her maternal line,' she said: '… that's always been a really bright line.'

Starr thinks these risks may be permissible in the face of passing on potentially fatal mitochondrial disease, but the case is less clear in the context of general fertility issues.

Professor Adam Balen, chairman of the British Fertility Society, also raised concerns over the experimental nature of pronuclear transfer. 'We would be extremely cautious about adopting this approach to improve IVF outcomes,' he said.

The child is not the first person to be born following the use of modern mitochondrial donation techniques. Last year, Dr John Zhang, founder of New Hope Fertility Center in New York, US, reported the birth of a baby conceived following mitochondrial donation using the maternal spindle transfer technique (see BioNews 871). The technique differs from pronuclear transfer in that the nuclear material from the intending mother's egg – prior to fertilisation – is placed into the denucleated egg of a healthy donor.

In this case the mother was at risk of passing on faulty mitochondria. However the birth attracted controversy since the procedure was carried out in Mexico where there are no federal laws regulating assisted conception, and thus no restrictions on the use of mitochondrial donation techniques.

The phenomenon of 'three person' babies is also not new - the late 1990s and early 2000s saw the birth of a small number of children in the US with genetic material from three people, following use of a technique called cytoplasmic transfer. However, the US Food and Drug Administration put a stop to use of the technique – which is different to mitochondrial donation – amid reports of genetic abnormalities in some of the children conceived in this way (see BioNews 108).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.