This Genetics Society podcast gives us a brief look into the history of genome editing and the various techniques that have been developed that have led us to where we are today. The podcast also implies that the future is still very much unwritten when it comes to what genome editing is truly capable of.

Initially I was surprised to find that 'a brief history of CRISPR: how we learned to edit the genome' was not a conversation between experts but instead, host, Dr Kat Arney, chronologically taking us through the history of genome editing. From the early uses of restriction enzymes to today's base editing techniques. At times it felt more like listening to an audiobook than a podcast. Jovial sound effects when there were radical discoveries to menacing music when more questionable events occurred. It was an addition I liked, as this made the podcast feel like a dramatic retelling rather than a history lesson.

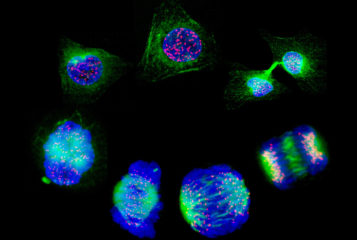

The podcast starts by looking over the first cases of genome editing and the early techniques that were developed. It swiftly investigates zinc finger nucleases in the 1980s and how ground-breaking they were, but not without limitations. Moving on to transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), I realised that this podcast was not that suitable for a non-scientific audience. While taking the time to explain concepts such as homologous recombination in DNA repair (a way of using undamaged DNA to repair a DNA break) and using clever analogies for genome editing (in comparison to editing a word document), it also used many technical terms colloquially, which might throw some people off.

When Dr Arney moved on to the discovery of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), I was shocked to learn that many scientists were not impressed by the technique at first. It is a tale as old as time in science, discoveries pushed aside if not deemed interesting enough, but when the experiments were repeated, the true implications became apparent. Considering that this occurred just under 20 years ago, to hear that such scepticism for new ideas was still prevalent was an eye-opener.

Then came the drama of the 'patent wars', which made sense once I thought about it – where there are discoveries, there is also money to be made.

Professor Jennifer Doudna and Professor Emmanuelle Charpentier (see BioNews 1067) were widely credited with discovering the CRISPR/Cas9 approach, yet they only filed for a patent for its use on prokaryotic cells. When Professor George Church and Professor Feng Zhang filed for patents just months later for the same technique but under eukaryotic cells, court battles and drama ensued over who gets to own and ultimately license the CRISPR/Cas9 approach. Sadly, this legal battle is still ongoing today.

Of course, you can't talk about the history of genome editing and not mention the now infamous case surrounding Dr He Jiankui. Having been sentenced to three years in prison and a substantial fine, he was the first to go against the law and have genome-edited embryos carried to term, resulting in the world's first twins who were supposedly HIV resistant (see BioNews 977).

I remember when this happened, my tutor asked whether I had heard the shocking news since it was relevant to my dissertation. This wasn't simply a matter of advancing genome editing, but was using its potential in untested and unethical ways, forever altering people lives. Unfortunately, He may not have been as successful as he initially stated as the cells were not 'edited uniformly' and so it is unknown how many cells were edited or if the twins have any immunity to HIV at all.

The podcast finishes by talking about the breakneck speed at which genome editing is progressing. A note that Dr Arney mentions is how what has been achieved today would have seemed like science fiction 100 years ago. I cannot help but think how correct she is and it has made me wonder, with the speed we are progressing, and the fact that genome-edited babies are no longer a 'question of if but when', what will it be like another 100 years from now.

Overall, it was an enjoyable listen. It covered everything in great depth, with storytelling that was enhanced by the music choices and narration by Dr Arney. As previously stated, I would recommend this to people who like genetics or have a scientific background, as some terms may be a little confusing for the uninitiated. But do not let that put you off – a bit of Googling never hurt anyone.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.