In a recent debate organised by the Progress Educational Trust in Parliament - 'Mitochondrial Donation: Is It Safe? Is It Ethical?' - I spoke about the ethical issues raised by techniques to avoid the passing on of inherited mitochondrial disorders, pro-nuclear transfer (PNT) and maternal spindle transfer (MST). It is claimed that because these new techniques will prevent terrible disease, save lives and are safe enough to use on humans, it would be unethical not to use them. The techniques, it is argued, are as acceptable as any transplant, or similar to replacing batteries in a camera.

Frances Flinter summed up such arguments in BioNews 773: 'Is it ethical to try and prevent the development of a treatment that might enable the birth of a healthy baby for a couple for whom there are no other options... and that could also avoid further tragedy in future generations?'

It is understandable that women with serious mitochondrial disorders who want children would want to avoid passing the disorders on to their own daughters and granddaughters. Nevertheless, I argued that it would be unethical to proceed and there are profound flaws in the above arguments.

First, it is not true that there are 'no other options' for prospective parents. Evan Snyder, who chaired a US Food and Drug Administration advisory panel on mitochondrial technologies, admits that 'there are alternative ways of preventing the passage of mitochondrial diseases to your offspring that are much less invasive and much more certain'. And, I would add, less risky. The majority of candidates for this 'treatment' who want (note, not need) a genetically related child can use pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) or IVF with a donor's egg, depending on the type of inheritance, as alternatives. A child would not be genetically related to the mother following egg donation, but would not be put at grave risk by an experimental, irreversible procedure.

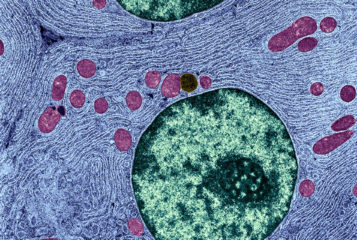

Second, is it ethical to prevent a 'treatment' that might 'enable the birth of a healthy baby'? Many consider that if it is safe, it is ethical. If so, this 'treatment' cannot be said to be ethical (at present). There is absolutely no guarantee that a healthy baby would be born from the techniques, as they are highly experimental - previously required tests using non-human primates were dropped after they failed to produce a single viable embryo. Other research found tissue-specific segregation and selective replication of mutated mitochondria in mouse embryos produced by a related technique (naming but a few safety concerns). The influence of mitochondria is poorly understood, but they do more than just provide cellular energy (like batteries) and they interact in many ways with the nuclear genome. Indeed, the severity of mitochondrial disease itself reflects the importance of the mitochondria for humans.

Also, this cannot be claimed to be a 'treatment' as is often argued. The techniques aim to prevent babies being born with mitochondrial disorders, but they treat no-one alive now or who will be born in the future with mitochondrial disorders.

Third, are the procedures ethical because they 'could also avoid further tragedy in future generations'? The lack of any long-term follow up of offspring born from monkeys (or those born of similar techniques) weakens this argument, particularly as results from mice and invertebrates suggest that many deleterious effects would not be revealed until adulthood. The scientific review panel convened by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) recommended that until more is known about the risk of daughters born following MST and PNT having mutated mtDNA themselves, these daughters are advised to screen their own embryos using PGD in order to select for embryos free of abnormal mtDNA as 'this has the potential to eliminate risk in subsequent generations'. Presumably this recommendation is because there is a real risk that her daughter and granddaughter could have abnormal mtDNA.

There is another future tragedy that these techniques could well create. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics notes: 'Many more egg donors will need to be found.... A shortage of egg donors is an acknowledged problem'. The truth is, this research requires hundreds of eggs from young, healthy women, raising both ethical and practical concerns. Egg donation is risky to women's health, from powerful hormonal treatments, injections and invasive surgery. There is little data, peer-reviewed research or follow up on women which assesses the long-term effects of egg donation. In order to obtain enough viable eggs for research and 'treatment', women are compensated, encouraging them to incur risks to their own health, not for their own medical benefit (unlike women accessing cheaper fertility treatment). This is dangerously close to being exploitative. A new advert for donors appeals to women's financial needs, calling for 'fit, healthy women between the ages of 21-35 years old who are willing to donate their eggs. Donors will receive £500 compensation for a completed donation cycle.' Will these women be informed of a report that just under half of 864 reported clinical incidents between 2010-2012 were due to ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome? And that 'each year approximately 60 instances of severe OHSS and 150 cases of moderate OHSS are reported to the HFEA'? Ironically, this is not far off the estimated number of women who could be candidates for the new techniques.

Fourth, is it ethical to 'try a treatment' on humans? Or put another way, to experiment on humans when serious safety issues have been identified (see BioNews 781)? It is argued - often justifiably - that no research is absolutely guaranteed to be safe, hence the need to move to human clinical trials. However these techniques are different to others permitted before. For one, there will be three adults with whom the baby shares a parental genetic connection, and genetic material from all three will pass down female generations. Second, modifying the germline will impact future generations in ways we do not know and cannot predict.

Manipulating the germline has long been regarded by Governments and international bodies as a Rubicon not to cross. A real fear is that once we do, manipulation of the genome will be regarded as acceptable for other disorders and purposes, as proposed last week for older infertile women to have children. Once we start to 'give chance a helping hand' and 'use the emerging knowledge from genetics to have not just healthier children, but children with better genes', as Julian Savulescu advocates, then genuine ethical concerns about eugenics arise.

Mitochondrial disorders range in severity but can occasionally lead to terrible disorders, including early death. I would love to see cures. However there is an equal or arguably greater chance that these experiments will tragically produce worse disorders or early death. I am concerned that some proponents of these techniques can over-hype claims of effectiveness, safety and cures. The precedent set in 2008 by scientists claiming that creating animal-human hybrid embryos was necessary to save thousands of lives should give cause for wariness when we hear similar claims repeated, based on equally experimental techniques. The risks these new experiments hold for the lives and health of human embryos, children and egg donors, and the unprecedented modification of the human germline, together provide a case for not crossing this Rubicon.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.