Key epigenetic factors regulating cell diversity in mouse embryos have been revealed in new research.

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin, Germany have used new techniques to determine the function of some key epigenetic regulators in the development of mouse embryos. Their work, published in Nature, found epigenetic regulator PRC2 is necessary for limiting the number of germline progenitor cells – cells that will develop into sperm or eggs.

'With the combination of new technologies we addressed issues that have been up in the air for 25 years,' said, senior author, Professor Alexander Meissner. 'We now understand better how epigenetic regulators arrange for the many different types of cells in the body.'

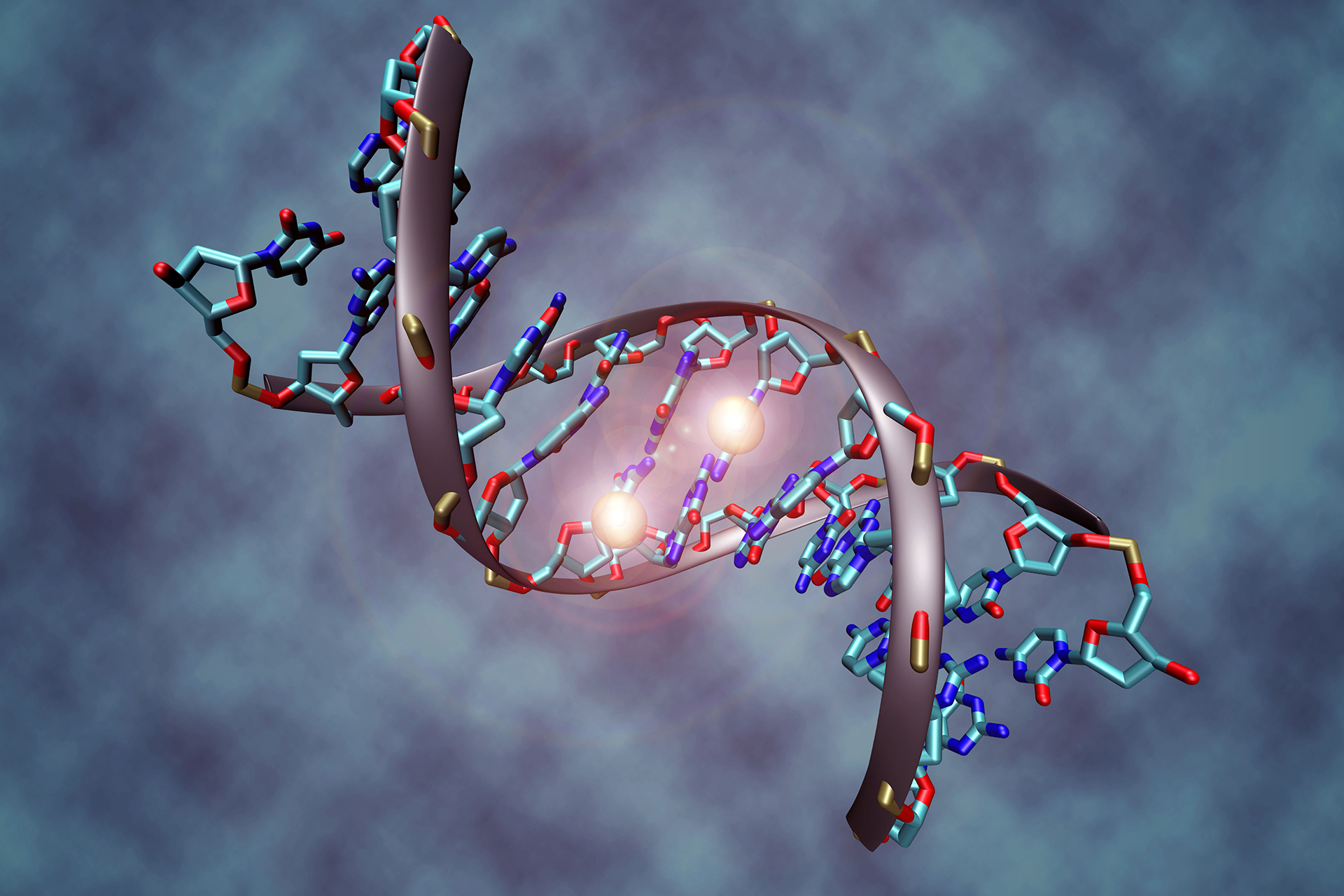

A fertilised egg cell develops into a whole organism, producing many specialised tissues and organs, while the genetic information inside each cell remains the same. Epigenetic marks play a role in making this happen by changing the 'packaging' of DNA without altering the DNA sequence. This 'instructs' cells what cell type to become by switching on or off certain gene.

Crucial regulator proteins control the location and timing of these epigenetic marks. Adding further complexity, these regulators are present in all cells but do different tasks depending on the cell type and timing. Until now it has not been possible to study these regulator proteins in detail.

The team used CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in fertilised eggs to remove single genes which code for epigenetic factors and observed the effects on development. After six to nine days they examined anatomical changes to the embryo and analysed gene expression in almost 280,000 individual cells.

Researchers said the single-cell analysis gave a 'high-resolution view' not possible from observing the embryo's appearance. Switching off a single regulator often led to a ripple effect causing changes to the activation of many genes in the network. Removing PRC2, a known epigenetic modifier, had a big impact on the embryo, causing an excessive number of germline progenitor cells, loss of shape and death.

Professor Meissner describes the potential of this new approach: 'Our method lets us investigate other factors such as transcription or growth factors or even a combination of these. We are now able to observe very early developmental stages in a level of detail that was previously unthinkable'.

This work also paves the way for more detailed investigations into epigenetic regulation, which is not only relevant for the development of embryos but also the formation of cancer.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.