| Twins: Identically Different

Organised by the Cheltenham Science Festival and King's College London Featuring Professor Tim Spector Winton Crucible, Imperial Square, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire GL50 1QA, UK, UK Tuesday 12 June 2012 |

|

Epigenetics. What on earth is that? You're probably aware that the genetics vs environment debate can still divide people to this day, but epigenetics is something that we haven't quite got around to talking about much in the public sphere.

And for good reason. It's not the most straightforward idea to get your head around. So my expectations of the reaction of the audience to Professor Tim Spector's talk at Cheltenham Science Festival this year, not having read his latest book on the subject, 'Identically Different: Why You Can Change Your Genes', was that of stunned silence and confusion. I was wrong.

What the audience got was what they actually wanted; an exploration of what epigenetics really means to them, rather than any mention of complicated mechanisms.

Professor Spector started by presenting what motivated him to study epigenetics in the first place. Having been involved heavily in carrying out twin studies he'd come across a lot of 'happy coincidences', but it's no surprise that eventually he came to appreciate something else: identical twins can have some very interesting differences as well. But, if they're genetically identical then how do you explain these major differences in, for example, the diseases they develop, whether they're religious, or what different personality traits they have?

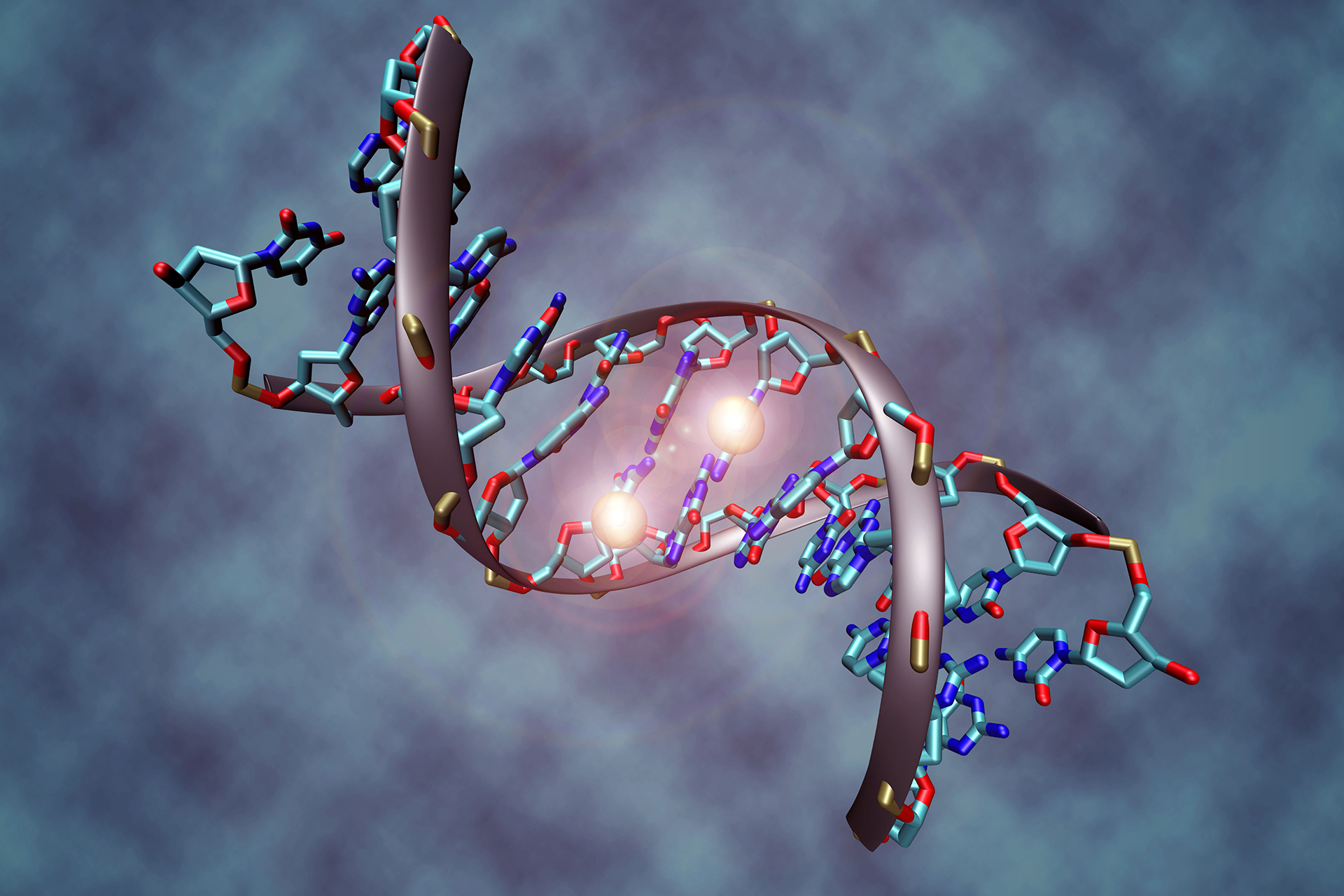

The answer lies, he revealed, in a third level, working at the interface between genetics and the environment: epigenetics. This, he explained, controls how your genes get switched on or off, and it's the genes that are on/off at any given time that can lead to differences between individuals, not just what versions of genes you have. Additionally, the combination of genes that are switched on/off at any given time is affected by environmental conditions and these changes can potentially be passed on for several

generations.

I was slightly disappointed that Professor Spector didn't go into detail about how epigenetics works, however, on reflection it was probably for the best. Instead he went through a series of interesting examples of how scientists have seen how certain traits or conditions can be affected by the environment that our parents and even grandparents experienced.

These included grandparents who had low food intake and who are more likely to have obese grandchildren; grandparents with higher alcohol in their diet who are more likely to have chubbier, ginger grandchildren; how chemical products from plastic containers can epigenetically affect brain development for several generations; and so forth. These were mostly experiments carried out in mice, of course, but twin studies in humans are also seeing similar links. In essence, 'you are what your grandmother ate'.

A big positive about the talk was that a clear attempt was made to convey the idea that while your grandparent's living conditions might contribute to a predisposition to any number of different traits or conditions, you can actively alter your own epigenetics as well.

The main example he provided was that of exercise in the battle against obesity. For example, the FTO gene which codes for a protein that acts a signal to your brain causing cravings for sugary and fatty foods, gets 'turned down' when you exercise, meaning you're less likely to want to eat 'bad' foods. Bacterial gut flora and faecal transplants were another example (yes, it is what you think).

Finally, the development of drugs to target epigenetic factors in cancer, obesity and dementia was highlighted.

The question and answer session was probably the best bit of the talk. There was plenty time put aside for all those big questions delving in to the likes of 'who am I?', 'what determines my fate?' and 'what impact will this have on our lives?'. The question of 'exactly how is this epigenetic detail stored?' only cropped up halfway through the Q&A, so clearly the content was captivating enough without throwing in confusing molecular biology. A very basic (and probably more incomplete than I would have liked) answer was given, but seemed to satisfy the inquisitor.

I generally find that these sorts of discussions can start getting into scary, deterministic waters, and unfortunately when the questions started turning on to a comment made about the effect of neglect on future generations, I admit I felt it had crossed the line. I could probably be put in the camp of a neglected child up until the age of seven, when I was adopted, so hearing people strongly supporting the notion that a neglected child is likely to grow up to be a neglectful parent themselves - and this effect was coded in to your very being, not something that you'd perhaps learned and could wilfully overcome - was a bit depressing. The whole 'cycle of broken families' has been in the limelight relatively recently, so strong feelings and opinions abounded. Also, given that the study in question was carried out in mice, more on the relevant caveats was needed rather than feeding on pre-existing prejudices. So despite the otherwise hopeful tone of the session, this let me down a bit.

Overall, the talk was very engaging. By using a topic that everyone is familiar with (twins) as a model to spark an understanding of the general principle behind what epigenetics is doing - if not how it's doing it - Professor Spector got the audience beyond the very two-dimensional nature vs nurture debate. However, to answer the question 'what on earth is epigenetics?' I'm sure many of the audience will be seeking out his book.

Buy Identically Different: Why You Can Change Your Genes from Amazon UK.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.