Israeli scientists have obtained early sheep embryos after transplanting whole ovaries that had been frozen and thawed. The researchers, based at the Institute of Animal Science, Agriculture Research Organisation, Bet Dagan, report that the ovaries were still working normally three years after the transplant. They say their findings, published in the journal Human Reproduction, show that the approach could one day be used to treat women facing premature ovarian failure (early menopause).

Whole ovary transplants have already been attempted twice in women, but not after first freezing and thawing the ovary. However, transplants of frozen, thawed ovarian tissue have shown promise, and two babies born after this procedure have been reported. And earlier this year, a US woman gave birth to a baby girl following an ovary tissue transplant from her identical twin sister. But the success rate of this approach is limited, partly because the egg-producing follicle cells can die before the transplanted tissue has established a new blood supply.

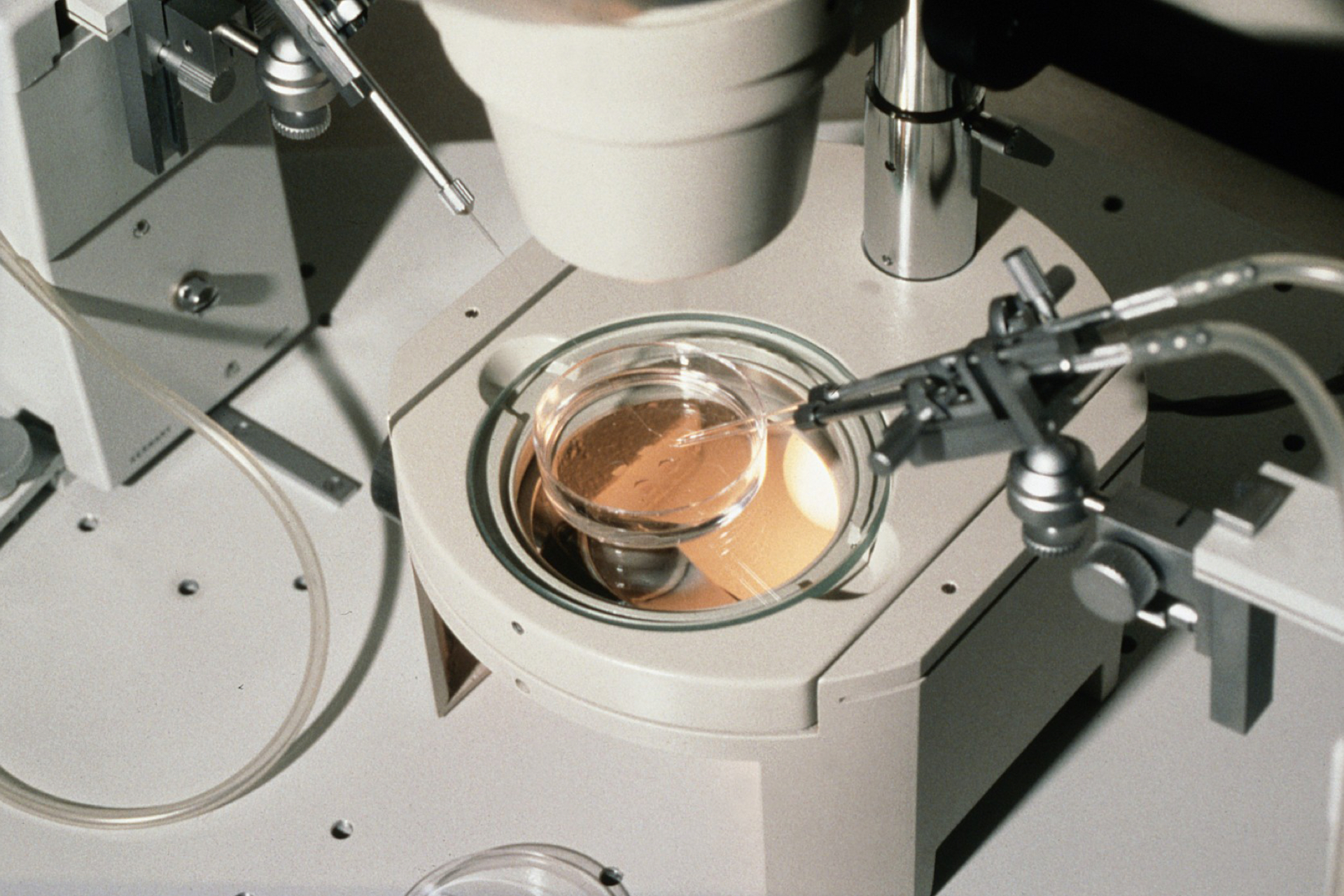

The Israeli team wanted to try and overcome the problems associated with ovarian tissue transplants by developing a new freezing technique that would allow the freezing of a whole organ. Their method allows them to control the development of ice crystals during the freezing process, which reduces the potential damage to the ovary and its blood vessels. They chose to work on sheep because their ovaries are similar to those of humans.

The researchers removed and froze the right ovary from eight animals and replaced them up to two weeks later, either at the original site or by grafting it onto the blood supply of a removed left ovary. In five sheep, normal blood flow to the ovary resumed immediately, suggesting that the transplant had succeeded. The team collected one egg (oocyte) from each of two animals, one of which yielded four more eggs four months later. They then 'tricked' these six eggs into behaving as if they had been fertilised (a process called parthenogenesis), and all developed into eight-cell embryos.

Team leader Amir Arav said they used parthenogenic activation because the success of IVF in sheep depends on the quality of the ram's sperm. 'This way, we knew that the development of the embryo depended solely on the quality of the oocyte', he said. Two years after the operations, scans of one of the treated sheep revealed that the transplanted ovary contained small follicles, and that its blood supply was still intact. 'This approach could revolutionise the field of cryopreservation for diverse human applications, such as organ transplants, as well as helping women who face the loss of their fertility', commented Arav.

Yehudit Natham, of biotech company Core Dynamics (which funded the study), said that although a lot of research remained to be done, in a few years the procedure could become 'a practicable option for women, such as young cancer patients, who would otherwise be left infertile by their treatment'. Allan Pacey, secretary of the British Fertility Society, told BBC News Online: 'Research work is proceeding on a number of fronts to give women more fertility preservation options - freezing eggs or slices of ovarian cortex - but it is still hard to tell which technique will finally enter mainstream clinical practice'.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.