The former Labour health secretary Frank Dobson, whose contributions in Parliament helped to pass the first Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, has died.

As a backbench MP Frank Dobson played a key role supporting PET's precursor organisation, the Progress Campaign for Research into Human Reproduction's campaign for regulated human embryo research to continue in Britain (1985-1990). He spoke against Enoch Powell's proposed 1985 Unborn Children (Protection) Bill which would have prohibited all creation and use of human embryos, except to help an infertile woman to become pregnant.

Dobson was among the MPs who emphasised the potential clinical benefits of preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD): screening embryos to prevent transmitting genetic disease. His arguments were key to the successful passing of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act and establishment of the HFEA (Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority).

Dobson also worked to fill the gap in statistics on infertility services in the early days of IVF, highlighted in the recommendations on human fertilisation and embryology made to government in the Warnock Report (1985). As Shadow Health Minister, he conducted a survey in July 1986 of the provision of infertility treatment in England, Wales and Scotland.

Continuing his support of the HFEA, he opposed its proposed merger with the Human Tissue Authority in 2006, convinced that 'this would be harmful because it would lead to the loss of the special focus which a single-function body can provide.'

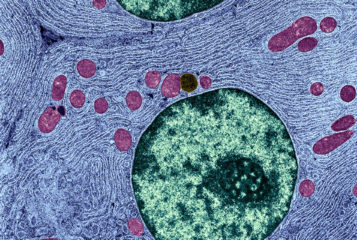

More recently Dobson worked alongside PET in the campaign to legalise the clinical use of mitochondrial donation. He reminded Parliament of the potential benefits of developing clinical procedures to prevent genetic conditions and urged that legislation should always be guided by the views of those most affected by the consequences of life-altering genetic disease.

In the debate in the House of Commons in February 2015, he emphasised the shared interests of patients and scientists: 'Parents are also willing to take the risks…The results are uncertain, but that is in the nature of both medicine and science. We cannot guarantee that it will work, but the people most involved in the matter and all the scientific advisory bodies in this country think that it will work, and we should take note of what they say.'

The fields of infertility and genetics continued to benefit from his dual commitment to scientific innovation and the public deliberation of new clinical possibilities. In a 2017 speech made about the HFEA he argued that, as much as scientific advancement is predicated on methodological innovation, it has also 'required the innovators to spell out what they are trying to do, how they are going about it and the benefits that could flow'.

Dobson's commitment to combating genetic disease with an eye to the needs and priorities of patients themselves lives on through the work done by the HFEA and PET today.

Dobson died on 11 November 2019, aged 79 and is survived by his wife, Janet Alker, and their three children, Sally, Tom and Joe.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.