|

BBC Radio 4, Wednesday 8 December 2010 |

This Frontiers programme challenged three genetic dogmas. First, hereditary material retains its identity from generation to generation. Second, each parent passes about the same number of genes to their offspring. Third, variations in the severity and pattern of hereditary disease are mainly due to different mutations in DNA. The presenter quoted a recent Observer headline on epigenetics: 'Why everything we were told about evolution was wrong!'

The programme began by challenging dogmas one and three by summarising detailed birth records from Holland in the 1940s and 1950s. The data showed that children of women who had been starved during their pregnancies (as a result of German blockades and the diversion of food to Nazi populations) were smaller than normal with an increased risk of developing schizophrenia, obesity and diabetes.

Next, an interview with Progress Educational Trust founder Professor Marcus Pembrey challenged dogma two. Twenty-five years ago, Professor Pembrey showed why children with Angelman and Prader-Willi (PWS) syndromes had different conditions, but an identical deletion on chromosome 15. Children with Angelman had inherited the deletion from their mother while children with PWS had inherited the deletion from their father.

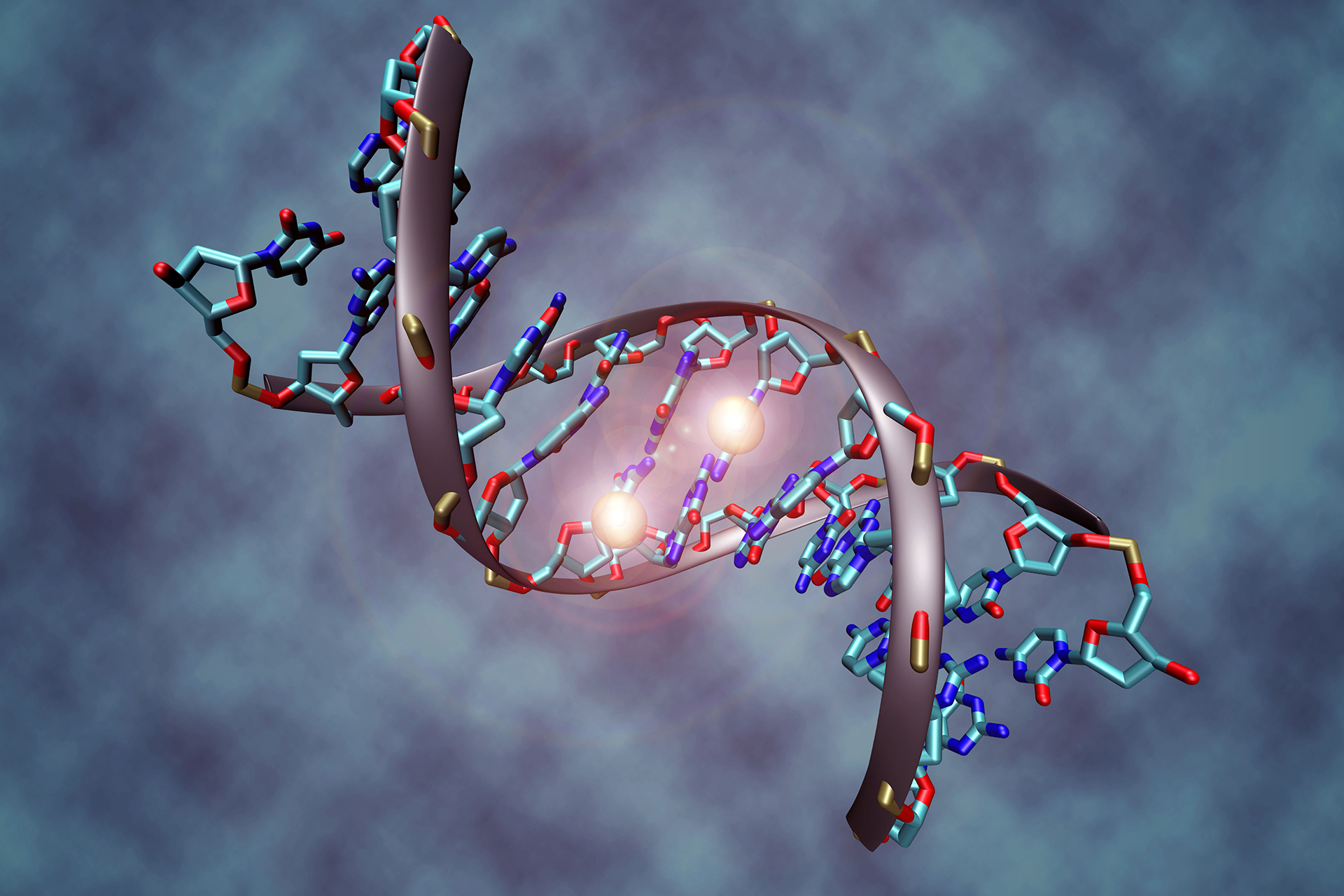

Professor Pembrey also explained genomic imprinting - a phenomenon where which genes are active depends on whether they are inherited from the father or mother. The presenter explained how imprinting occurs when the DNA is 'tagged' through a process called 'DNA methylation'.

The next scientist, Dr Alan Brown of New York, discussed how methylation of a gene (IGF2) influenced the behaviour of women starved at a critical point during their pregnancy. Dr Jonathan Mill from the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, meanwhile, talked about studies in mice suggesting the age of a child's father influenced the likelihood they would have autistic traits.

The programme also presented data from studies in North Sweden where - in the past - there were long winters and a higher risk of starvation. These studies showed the grandchildren of fathers starved in their mid-childhood growth periods (about age six to nine) showed differences in longevity from normal. Grandfathers with a good food supply in their mid-growth period were more likely to have grandchildren with diabetes.

Professor Pembrey and colleagues are actively involved in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), which set out to explore the effect of epigenetic and other mechanisms on growth measures like weight. ALSPAC found that - if a child's father started smoking before his puberty growth spurt - his sons were likely to have a greater body mass index at age nine.

Finally we heard from Dr Michael Skinner, a molecular epigeneticist from Washington State University. He seemed dismissive of the innovative epidemiological studies mentioned above when he said they were 'quite useful in that they proved that the phenomena exist'. In comparison, he said molecular epigenetic studies explain the mechanism by 'direct analysis'.

Dr Skinner, rightly, said molecular epigenetic studies and 'early stage diagnostics based on epigenetics' might lead to treatment strategies. The programme finished with a brief mention of how thinking has now gone 'full circle' - challenging some Darwinian evolutionary thinking. Epigenetics seems to suggest Lamarck's 'inheritance of acquired characteristics' is true.

This was an excellent programme and the presenter, Adam Rutherford, is to be congratulated on his lucid explanation. My slight disappointment is some molecular epigeneticists seem unaware of the value of collaborating with clinicians, epidemiologists and even affected families.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.