A sociologist quoted by the Daily Mail has claimed that an egg-sharing scheme offered by our own and other fertility clinics 'sounds like bribing women to freeze their eggs'. Such schemes, said the University of Buckingham sociologist, seemed no more than a 'marketing ploy' with no regard for 'the long-term consequences'.

Such tired arguments, although made within the context of a new fertility preservation service and the contemporary technology to achieve it, are all too familiar to me. More than 25 years ago, when my late colleague Dr Eric Simons and I took the first steps in what would become known throughout the world as 'egg sharing', there were many, including the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), who made very similar objections – that our novel egg donation scheme was exploitative, that it favoured the egg recipient (who paid), that subsidised IVF in return for shared eggs was simply an inducement, a payment in all but name.

But conversely the arguments in favour of egg-sharing as a source of donor eggs were also the same then as they are today in the 'freeze-and-share' schemes misguidedly criticised in the Daily Mail. From those first days in 1992, when a group of five patients in north-east England broached the idea of free IVF in return for a share of their eggs for donation, Dr Simons and I performed study after study to show that the objections were no more than a knee-jerk reaction, with little or no scientific evidence.

For example, a study of 246 egg-sharing cycles performed at the London Women's Clinic before 2009 found high and comparable birth rates per transfer between egg sharers and egg recipients (45 percent versus 32 percent), with no apparent outcome in favour of one or the other. It was clear from these and other studies at the time that women who share their eggs with a recipient do not compromise their own chance of success – and this is even more evident today with the uptake of single blastocyst transfer, embryo storage and cumulative live birth rates.

Similarly, research that we completed in 2012 with the Centre for Family Research in Cambridge involving 86 egg-sharing patients (donors and recipients) found 'an overwhelmingly positive assessment', with almost no differences in response between those who shared and those who received. This underlined what we had always found, that coercion through the 'inducement' of subsidised treatment is rarely the sole reason for sharing. Time and again studies from other countries have shown that egg-sharing women are often motivated by altruism, the latter a commonly found response of routine egg donors.

Nevertheless, egg-sharing has been addressed on three occasions by the HFEA, which was cautious and seriously considered whether the subsidy of free IVF treatment given to sharers was actually a financial inducement and thus outside the letter and spirit of the UK's regulations. That concern was first resolved in 2000 when the HFEA endorsed egg-sharing and formally aligned it with egg donation. Again, in 2008 the HFEA reaffirmed that 'donors may continue to receive benefits in kind'. And most recently, in 2011, egg-sharing was again endorsed by the HFEA in its substantial report on gamete donation.

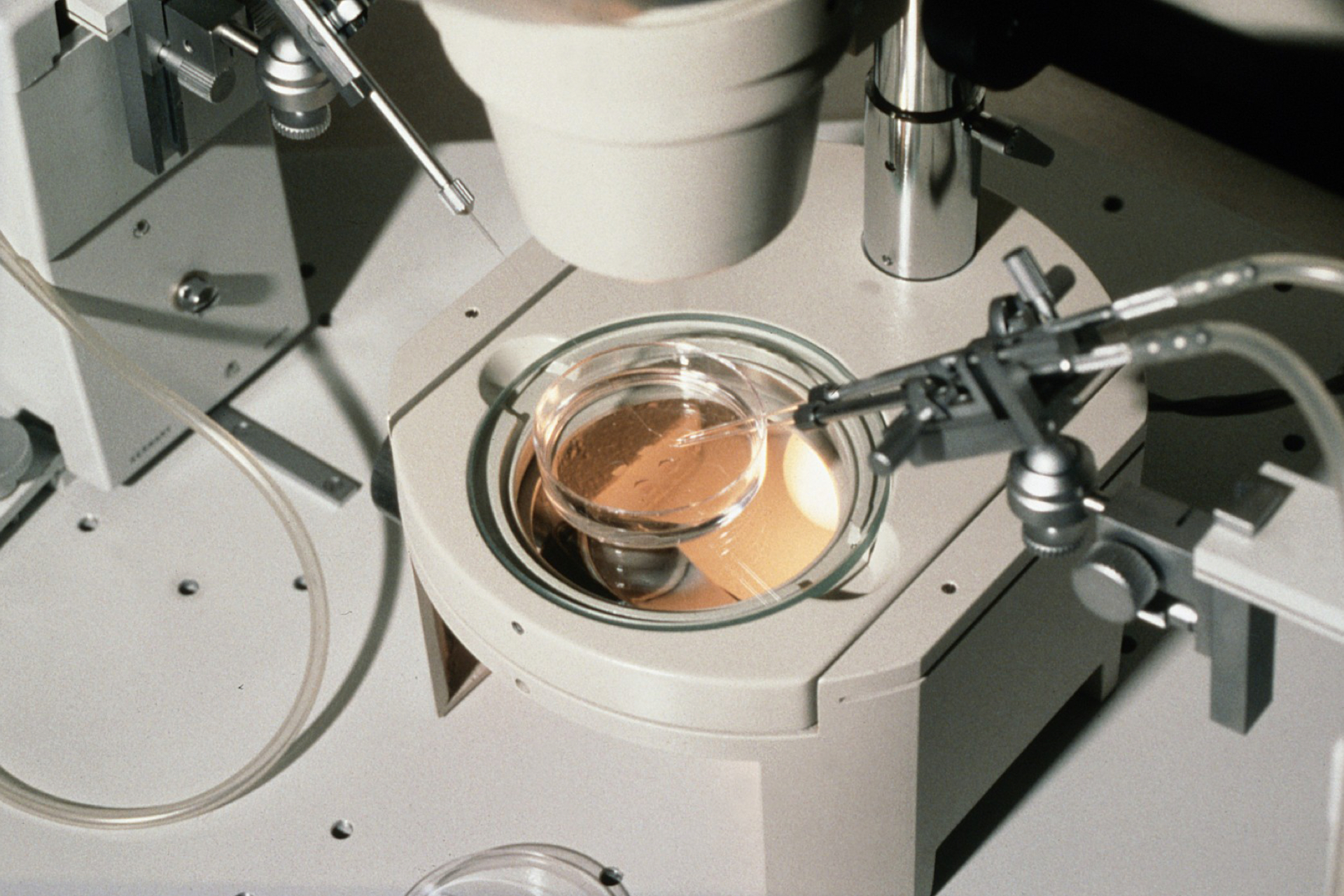

The arguments for and against subsidised egg freezing, as the Daily Mail implies, are still about 'inducement' – but now the technology has moved on. The uptake of egg and embryo vitrification has finally allowed the viable cryopreservation of oocytes, which up to a decade ago was simply not possible with traditional slow-freezing methods. Studies have shown unequivocally that the viability of vitrified oocytes (in egg donation) is just as great as that of fresh. Vitrification has thus raised the potential for egg banking for egg donation and for fertility preservation for both medical and elective social indications. Today, it is vitrification which has moved the practice of egg-sharing forward.

The demand for donor eggs in Britain continues to rise, with more and more couples postponing their first pregnancies and, as a result, a greater prevalence of age-related infertility. For these women whose ovaries have ceased to function as before, egg donation remains their only chance of conception and pregnancy. The rate of successful pregnancy for a 43-year-old woman is around 50 to 70 percent with donor eggs, but only around 5 percent with her own eggs.

An HFEA report on egg donation treatments from 2014 to 2016 shows a 49 percent increase in cycles using donor eggs since 2011, a rapidly climbing treatment curve plotted against a background of ever-ageing patients, more embryo and oocyte freezing, and improving success rates in donor cycles. But as yet, the domestic supply of donor eggs cannot meet this rising demand, with the result that overseas treatment is often the easiest (or only) option.

At the same time, we have seen a rising demand from UK women opting for elective or 'social' egg freezing – usually as insurance against the inevitable decline in female fertility after the age of 35. The increase in egg freezing procedures at the London Women's Clinic has been dramatic, up from just six treatments in 2012 to 186 in 2016, and 309 in 2018. These figures were reflected in a survey this year from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists which found that 11 percent of women questioned had frozen or considered freezing their eggs, with a further 34 percent saying they would consider this in the future (see BioNews 991).

The HFEA's latest report on egg donation did not address the technique of freeze and share, and there are no studies as yet of those taking part. But, as more and more women turn to elective oocyte freezing, some questions must be addressed, not least the ten-year limit to storage time (see BioNews 991).

For now, however, it seems reasonable to hope that the objections to subsidised IVF treatment for egg-sharers are not raised yet again with subsidised egg freezing in a renewed ethical debate. For just as 20 years ago egg-sharing provided opportunities for women to receive IVF treatment without cost, so now schemes like freeze and share provide the same opportunities for fertility preservation and delayed IVF for women who cannot afford the cost of treatment.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.