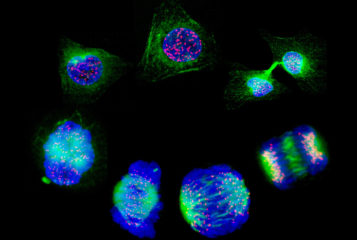

Chinese scientists have successfully used genome editing to correct mutations in viable human embryos for the first time.

The study used CRISPR technology, which has previously been used to edit genes in non-viable human embryos (see BioNews 799 and 846). These attempts had very low success rates but it was not known if this was because the embryos had an extra set of chromosomes.

'[This study] does look more promising than previous papers,' Dr Fredrik Lanner of the Karolinska Institute in Sweden told New Scientist. Dr Lanner's team is also using CRISPR to edit genes in human embryos.

The team, led by Jianqiao Liu at the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, used eggs leftover from IVF procedures and fertilised them with donor sperm from two men to create six embryos. One of the sperm donors had a mutation called β41-42, which causes beta-thalassemia, while the other donor had a mutation in the G6PD gene. This is a common cause of favism – a disorder in which eating foods like broad beans can trigger the destruction of red blood cells.

Two of the resulting embryos had mutations in the G6PD gene, and four embryos had the β41-42 mutation. The researchers injected them with the CRISPR machinery and allowed them to develop for two days. They then analysed the embryos' DNA to check whether the mutations had been successfully corrected.

The mutation in the G6PD gene was successfully repaired in one embryo. In the other embryo, it was corrected only in some cells, forming a mosaic embryo.

The β41-42 mutation was also only partially corrected in one embryo, forming another mosaic. CRISPR induced another mutation in another embryo, and the technique did not work at all in the two remaining embryos.

Speaking to New Scientist, Professor Robin Lovell-Badge of the Francis Crick Institute described the results as 'encouraging'. However, he warned that the numbers are far too low to make strong conclusions.

Before the technology could be used in the clinic, researchers would need to find a way to prevent mosaic embryos, for example by editing genes in sperm and eggs before IVF, rather than editing embryos.

There are also many ethical concerns over the use of genome-editing technologies. A recent report by the US National Academy of Sciences (see BioNews 889) advised that genome editing should be be restricted to genes that are known to cause or predispose people to serious conditions, and should only be carried out the absence of other alternatives – for example when none of a couple's embryos will be free of inherited disease.

The research was published in the journal Molecular Genetics and Genomics.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.