It didn't take long after starting to write for BioNews to realise that research into fertility and conception is less about understanding their features or mechanisms, and far more about our undeniable, unassailable right to family.

Consequently, it is about enabling this right to be recognised when, whether due to biological or social reasons, difficulties may arise. I have written many news articles involving those seeking to achieve this, from research into re-inducing fertility in menopausal women (see BioNews 1060) to bureaucratic blocks delaying passport applications for surrogate-born children (see BioNews 1063). However, none of these stories have had such a striking effect on me as that of posthumous reproduction.

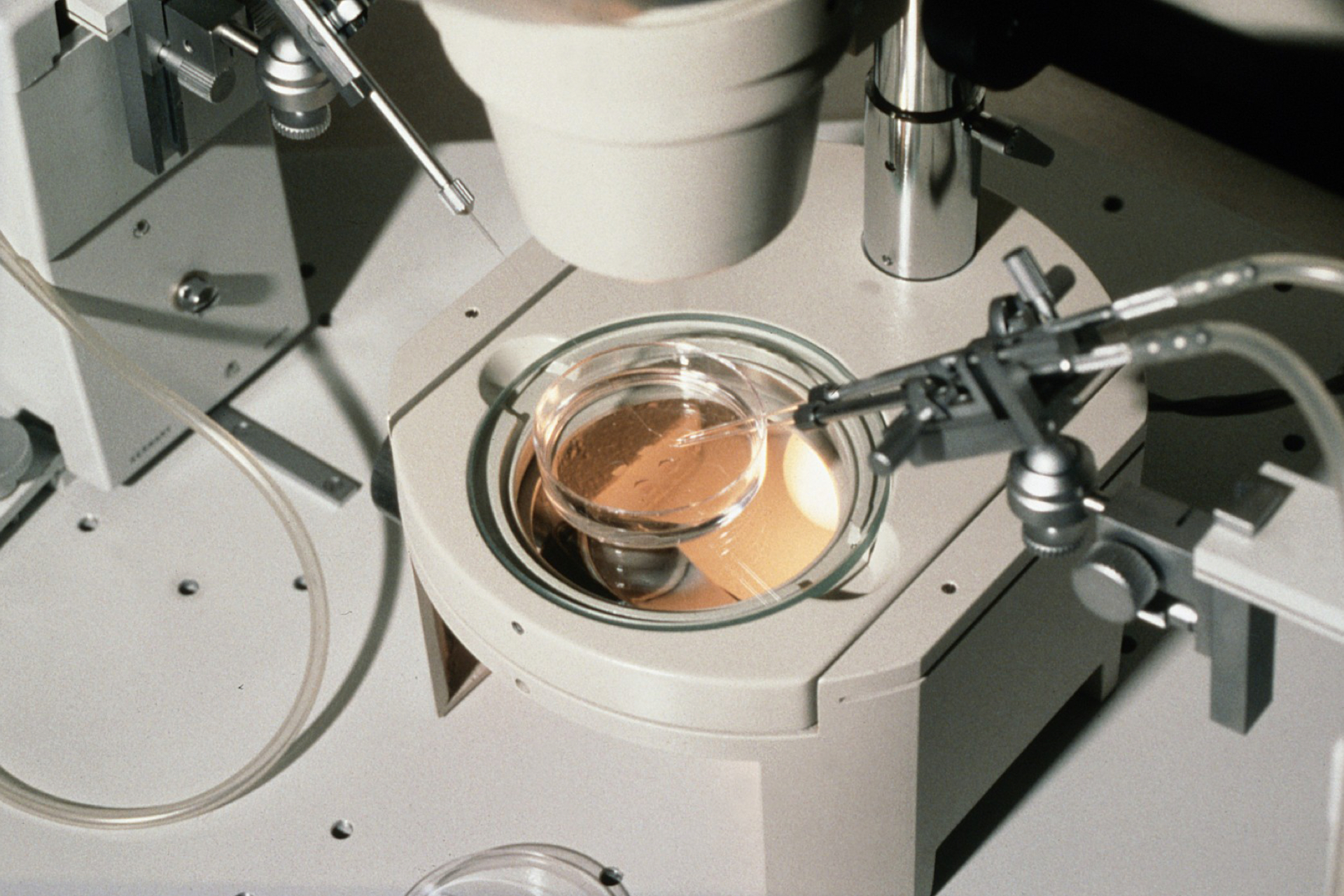

The subject of 'Creating life after death', the astonishing episode by Viv Jones published as part of the BBC World Service's 'Heart and Soul' podcast, 'posthumous reproduction' refers to the use of a person's frozen eggs or sperm for conception following their death.

Specifically, the episode focuses on the story of Shira Malka, an Israeli child whose father, Baruch, died from cancer seven years prior to her birth. Whilst this process is technically feasible in many countries, the ethical considerations it presents have created a legal minefield which must be navigated by those wishing to carry out the wishes of their deceased relatives. As Jones says of Baruch, 'Shira's birth was his dying wish'.

What I found so poignant about this story, and what was presented so beautifully in the podcast, was the unique family dynamics enabled by posthumous reproduction, where the status of the deceased as a parent of the child is maintained. As explained by Irit Rosenblum, the pioneering lawyer who developed the 'biological will' and has enabled the births of hundreds of children through posthumous reproduction, women who choose this approach as opposed to anonymous sperm donation 'have the opportunity to win a full family'. As a result, whilst Baruch's parents, Julia and Vlad Pozniansky, heartbreakingly lost their son, they were subsequently able to gain not just a granddaughter, but one who embodies Baruch himself.

And we see that, although Shira never met her father, he pervades her life like any father would. The episode opens with Shira, along with her mother Liat, proudly displaying the trophies her father won for table tennis. Julia remarks about how she and her granddaughter share their blue-grey eyes and fair hair, and how they visit the nearby forest where monkeys can roam free. Shira and Baruch have this deep connection, arguably a relationship, stemming entirely from the family which has been formed around posthumous reproduction and, especially during my first listen, this achievement felt utterly magical.

Israel, where having babies was described as a 'national imperative' by the Israeli bioethicist Professor Vardit Ravitsky, has long been a driving voice in the field of progressive family planning. This is grounded both in Israel's Jewish traditions, where the mandate 'go forth and multiply' is the first divine order ascribed in the Bible, as well as recent history, where the harrowing legacy of the Holocaust is still very real and pervasive.

Intriguingly, the concept of posthumous reproduction received almost overwhelmingly positive consensus from representatives of multiple disciplines, including rabbis. They cited the ancient Jewish tradition of yibbum where, if a man dies childless, his widow is encouraged to marry his brother, who will subsequently father children in the deceased man's name. Whilst undoubtedly a radical modernisation of the initial practice, the rabbis argued that the sentiment, and the prioritisation of the deceased brother's role in fathering children, was still reflected.

Professor Ravitsky admits that this practice does have a distinctly Israeli feel. Whilst the handful of countries who enable posthumous reproduction do so with strict regulation, namely explicit written consent, the Israeli culture often allows 'presumed consent', in which a letter, a text, or even a nonchalant conversation could potentially be sufficient (cases of which Rosenblum has, and vows to continue to, take on). This is a tradition which, Professor Ravitsky admits, would be difficult to convince others of, but in Israel opposition is particularly sparse, as the conversation is dominated by emotive stories of sons killed during their mandatory military service.

Admittedly, for much of the episode, opposition to posthumous reproduction was presented somewhat tamely. Defence took the form of the standard baggage which all children are prone to and, in my opinion, omitted the significant value of the unconventional family structure forged as a result.

That is until the introduction of Elan Neumann, a musician from Jerusalem who is deeply opposed to the practice and, in a literal jaw-dropping twist for me, is revealed to be the son of Professor Ravitsky. In addition to raising issues about the rights of the deceased being neglected, he, convincingly, proposes that fathering means more than a sperm contribution. 'I want to be there as a father to raise and shape my offspring' he tells his mother in a way you can hear has been honed after years of animated, yet undeniably affectionate, conversation. 'To have biological offspring', he argues, 'that is something completely different'.

Interestingly, whilst Professor Ravitsky acknowledges her son's position, and indeed claims his suggestions are the only dissenting points she is convinced by, as soon as she reconsiders the mother's perspective, she is instantly reassured of her own position. This raises a fascinating question about for whom posthumous conception is designed. The benefits for the new parent and child are explicit, as are those of the grandparents who may have driven the process. But other than when explicitly stated, is it beneficial for the deceased, and if not, then should it be? I think that this is a deceptively simple question to answer and, as Rosenblum says, 'we have to make better lives for those who are still with us'.

'Creating life after death' works partially because it has all the makings of a great story – there are trials and tribulations, hope and heartbreak, determined and inspiring lead characters, loving yet feuding families, and what I, personally, would call a gleefully happy ending. However, it also taps into something tangibly human at the centre of our right to a family. It is understood by everyone involved that Shira's life and Baruch's death are intertwined, but that does not at all discount from the joy which has been brought to so many more than could have been possible. To hear this displayed with such sensitivity was an utter pleasure.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.