Research has found that smoking can leave long-lasting epigenetic changes on the genome.

'Our study has found compelling evidence that smoking has a long-lasting impact on our molecular machinery, an impact that can last more than 30 years,' stated Dr Roby Joehanes of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School in Boston, lead author of the study, which was published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics.

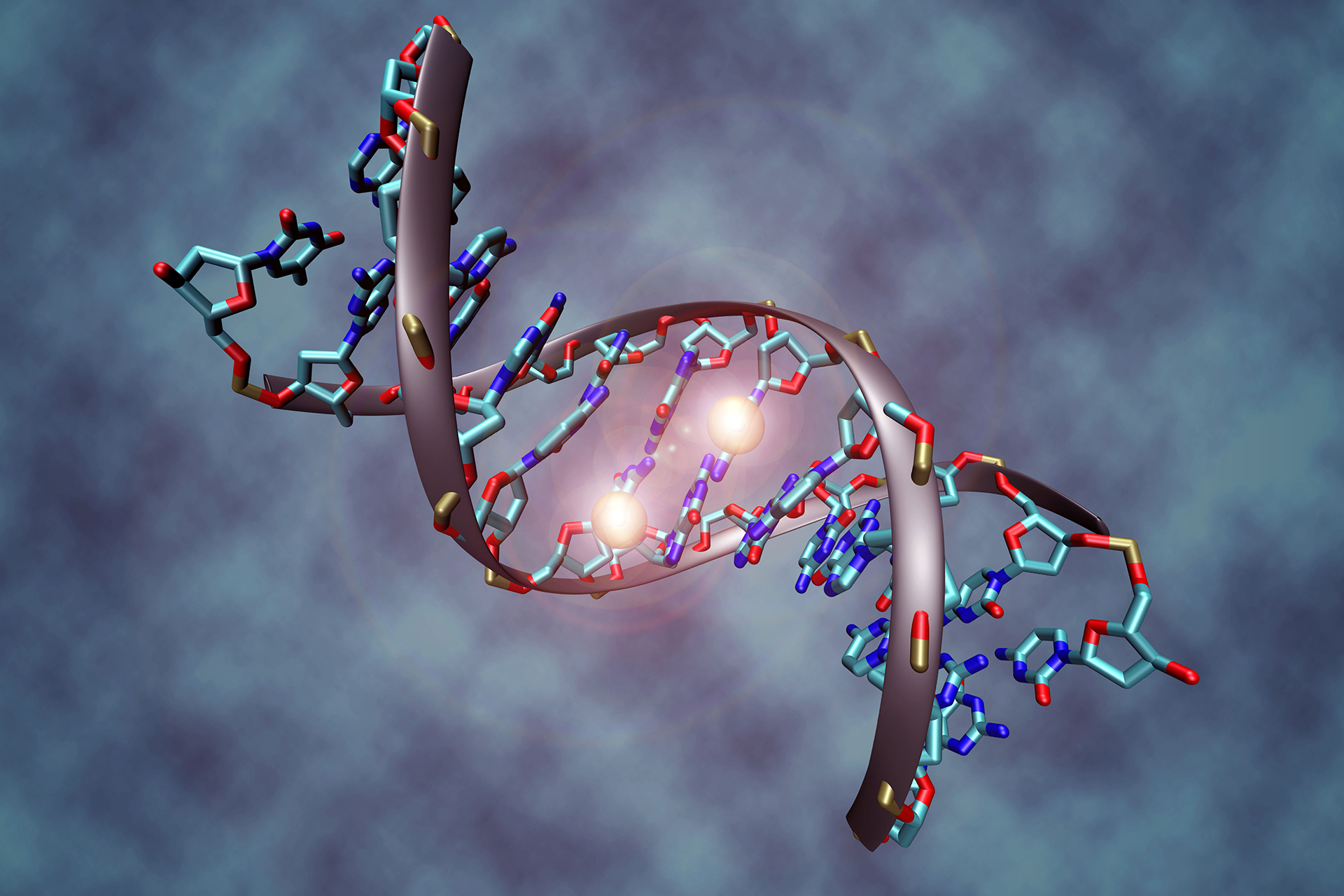

Scientists know that former smokers are at increased risk of developing some cancers and heart diseases, but the mechanisms responsible have been unclear. This study suggests that epigenetic changes, which occur within the genome and influence gene activity without changing the DNA itself, are a possible cause of this.

The researchers focused on patterns of DNA methylation across the genome in 15,907 patient samples across 16 cohort studies. Methylation is an epigenetic process which cells use to control gene activity. The cohorts comprised 2433 current, 6518 former and 6596 never smokers. Current smokers were defined as patients who said they smoked at least once a day sometime over the last year, while former smokers were individuals who had stopped at least one year before blood samples for the investigation were obtained.

The genomes of current smokers showed 2623 sites of DNA methylation, compared to never smokers. The authors suggest that this corresponds to 7000 potentially affected genes, approximately a third of the human genome. Furthermore, many of these genes have been associated with smoking-related disease traits including pulmonary function, cancer, inflammatory disease and heart disease.

'We don't really know whether it means "damage" to the DNA,' said senior author Dr Stephanie London, chief of the Epidemiology Branch at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. 'That requires more study, using data outside what we have here. What we're saying is that it's a change to your DNA that can have a downstream effect on what genes are expressed at what levels.'

Additionally, comparison between former and never smokers identified differences in DNA methylation at 185 sites across the genome. As found previously, the strongest differences occurred at sites associated with smoking-related disease traits. In some individuals, this difference was present 30 years after cessation of smoking.

Given the large number of genes potentially affected, the research did not focus on individual gene changes and the possible health effects. Future investigation is likely to focus on the potential therapeutic implications of these findings to target prevention and treatment of tobacco-related disease. Alternatively, these findings could be used to develop diagnostic tests to evaluate the health effects of a patient's smoking history, or help rule out smoking as a cause in other studies of environmental influences on health.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.