A large international study has revealed that smoking during pregnancy may chemically alter the DNA of the developing fetus.

As part of the newly developed Pregnancy And Childhood Epigenetics (PACE) consortium, researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 13 smaller studies, combining information from 6685 newborns and their mothers, who were of mainly European descent.

Based on questionnaires given to the mothers, 13 percent of the newborns had been exposed to 'sustained' (daily) maternal smoking during pregnancy, 25 percent were exposed to 'any maternal smoking' during pregnancy, and the remaining 62 percent were born to non-smokers.

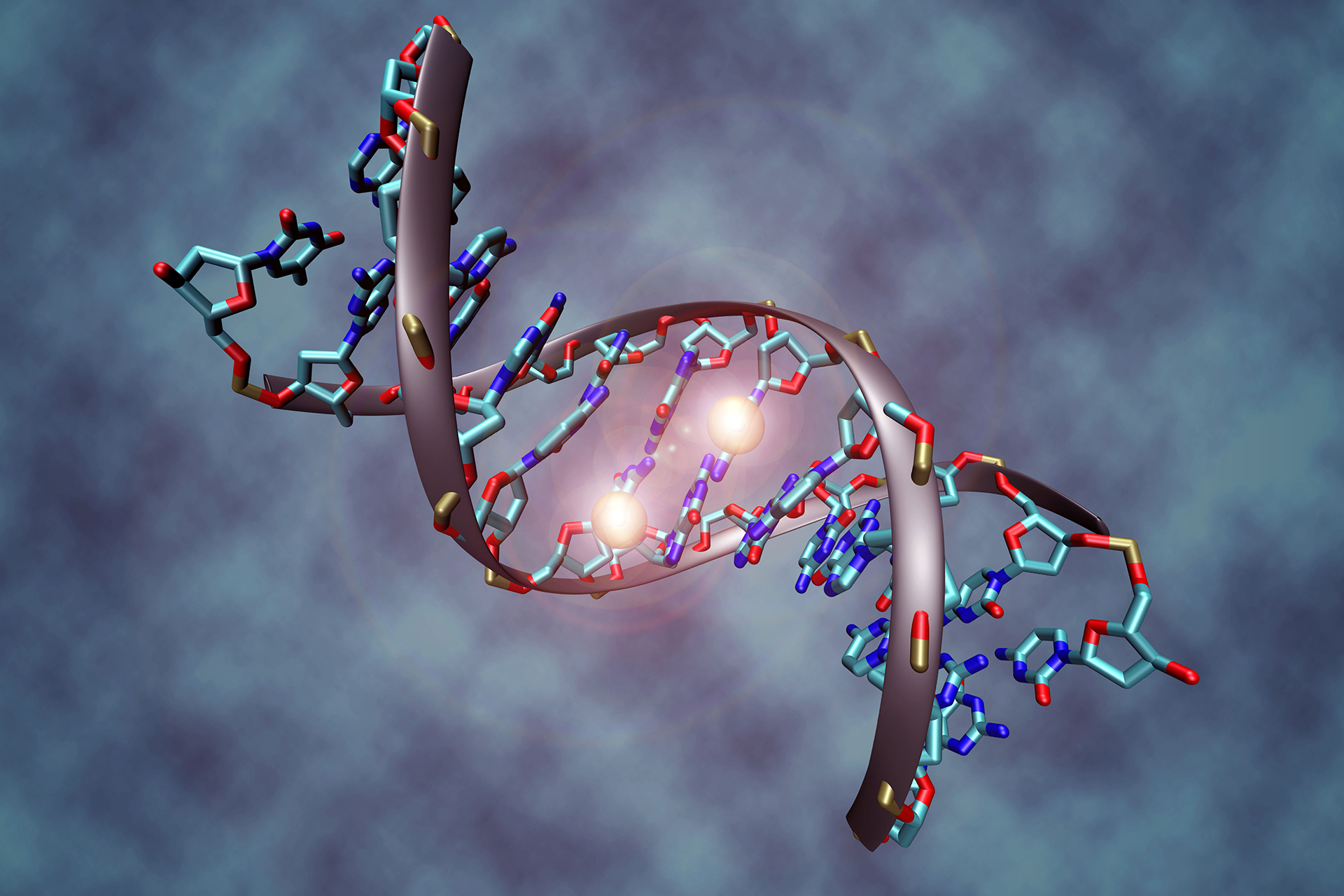

Using blood taken from the umbilical cord after birth, the researchers looked for differential patterns of epigenetic modifications – chemical alterations, such as DNA methylation, that do not affect the actual sequence of the DNA but do affect the way genes are expressed – between the three groups of newborns.

The research teams identified 6073 places in the DNA of children born after 'sustained exposure' to maternal smoking that had different modifications compared with babies born to non-smoking mothers. The location of these epigenetic marks was reported to mirror those seen in adult smokers.

Among the newborns whose mothers had smoked during pregnancy, there were 4653 places in their DNA that were differently modified.

Co-senior author Dr Stephanie London, an epidemiologist and doctor at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), said: 'I find it kind of amazing when we see these epigenetic signals in newborns, from in utero exposure, lighting up the same genes as an adult's own cigarette smoking. This is a blood-borne exposure to smoking – the fetus isn't breathing it, but many of the same things are going to be passing through the placenta.'

Dr Bonnie Joubert, who also works at the NIEHS and is the study's lead author, noted that 'many signals tied into developmental pathways' and explained that many changes were seen in, or nearby, genes relating to lung and nervous system development, smoking-related cancers, and birth defects such as cleft lip and cleft palate.

The team also looked at 3187 older children with an average age of 6.8 years. Eight percent of these children had been exposed to 'sustained smoking' during pregnancy, and another 13 percent had been exposed to 'any maternal' smoking during pregnancy. They found that many of the DNA changes seen in newborns were still seen in older children, indicating that such chemical modifications persist into later childhood.

The precise reasons why maternal smoking can lead to adverse health effects in their children remain poorly understood. However, this study – the largest of its kind – adds support to previous suggestions that it may be related to epigenetic changes.

Dr London said: 'We already knew that smoking is related to cleft lip and palate, but we didn't know why. Methylation might be somehow involved in the process.'

It cannot be determined from this study alone whether the observed epigenetic differences are harmful and actually cause smoking-related diseases in children. Future work is needed to build on these results to determine if, and how, the observed DNA modifications could impact on child development and disease.

The study was published in the American Journal of Human Genetics.

Sources and References

-

Smoking During Pregnancy Affects Infants' DNA Methylation Patterns, Study Finds

-

Mom's smoking alters fetal DNA

-

Smoking while pregnant changes baby's DNA, mounting evidence shows

-

Mother's smoking during pregnancy affects babyÔÇÖs DNA

-

DNA Methylation in Newborns and Maternal Smoking in Pregnancy: Genome-wide Consortium Meta-analysis

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.