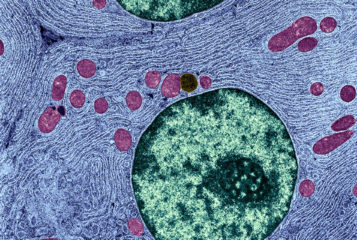

A study has identified a potential problem with mitochondrial donation, an IVF technique that aims to avoid the transmission of faulty mitochondria from mother to child.

The technique potentially allows mothers with mitochondrial mutations to conceive using a donor egg whose nuclear material has been removed and inserting the mother's own nuclear material. During this transfer, a small number of the mother’s faulty mitochondria are transferred to the donor egg as well.

This latest study suggests that, in certain circumstances, these carried-over mitochondria can outcompete the healthy mitochondria.

'It would defeat the purpose of doing mitochondrial replacement,' Dr Dieter Egli, of the New York Stem Cell Foundation and a senior author of the study, told Nature News.

In the study, published in the journal Cell Stem Cell, Dr Egli and his colleagues carried out mitochondrial replacement by transferring nuclei in human egg cells, which were then turned into embryos by parthenogenesis. They used the resulting embryos to generate stem cell lines in the lab.

Dr Egli's team found that, immediately following the transfer, the cells contained just 0.2 percent of carried-over mitochondria. However, after growing the stem cell lines in the lab, this ratio jumped to 53.2 percent in one cell line before dropping back to one percent. Around half the time, colonies derived from that cell line had increased levels of the faulty mitochondria.

Dr Egli told Nature News that he suspects this resurgence happened because one mitochondrion was able to copy its DNA faster than other mitochondria. This is more likely to happen when large DNA-sequence differences exist between the donor's and recipient's mitochondria. He suggested that, should mitochondrial donation reach the clinic, donors should therefore be matched to ensure that their mitochondria are broadly similar.

Professor Mary Herbert, a reproductive biologist at Newcastle University who was not involved in the study, told Nature News that these stem cell lines are not directly comparable to the development of an embryo in the uterus, making their relevance 'questionable'. 'They are peculiar cells, and they seem to be a law unto themselves,' she said, adding that levels of mutant mitochondria can fluctuate wildly in stem cell lines.

'Maintaining the stem cell state for many months in the lab does not reflect what happens during normal embryonic development where it exists only transiently,' she added.

One in 5,000 children are born with mitochondrial disease, which can cause stunted development, neurological disorders, heart disorders, and stomach and digestive problems. The UK Government was the first to legalise mitochondrial donation last year (see BioNews 792) although the HFEA has yet to grant a licence to any IVF clinics to perform it.

Sarah Norcross, director of the Progress Educational Trust, which publishes BioNews, pointed out that on thw whole the study's findings are 'largely reassuring'.

'There is now robust evidence that novel combinations of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA do not lead to a problem of mismatch, which was a concern raised by some scientists in relation to the safety of mitochondrial donation,' she said.

Sources and References

-

Genetic Drift Can Compromise Mitochondrial Replacement by Nuclear Transfer in Human Oocytes

-

Avoiding mixtures of different mitochondria leads to effective mitochondrial replacement

-

Three-person embryos may fail to vanquish mutant mitochondria

-

Why ÔÇÿthree-parent embryoÔÇÖ procedure could fail

-

'Three-parent babies' technique to prevent genetic diseases hits snag

-

Is three-parent IVF therapy safe? Fears for controversial technique after study shows faulty DNA can slip into eggs

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.