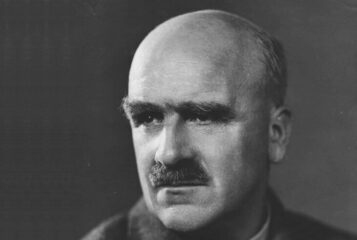

One hundred years ago, JBS Haldane, the pioneering British geneticist, gave a lecture at Cambridge entitled Daedalus, or Science and the Future, where he introduced the idea of assisted reproductive technology into the public imagination.

The lecture was named after the craftsman from Greek mythology chosen by Haldane as the embodiment of biomedical innovation (wooden cows included). While other mythological figures were punished for their audacious deeds, Daedalus was not. He created a labyrinth but was then able to escape from it.

The Progress Educational Trust (PET) is also dedicated to promoting the public understanding of science, illuminating a path through the labyrinthine maze of issues presented by reproductive technologies, explained Sandy Starr, deputy director of PET. He was introducing the event '100 years of Daedalus: The Birth of Assisted Reproductive Technology', which PET produced in association with the Anne McLaren Memorial Trust Fund (McLaren was a student of Haldane's) and Cambridge Reproduction.

The event brought together a range of experts to explore Haldane's legacy, and what the next 100 years might have in store for reproductive technology. To understand where technology is going, it is important to know where it came from, said Starr.

First to speak was Samanth Subramanian, author of Haldane biography 'A Dominant Character', who gave an account of Haldane's early years. He framed the issues explored in the Daedalus lecture in the broader context of the late 19th century, taking us through the horrors of the First World War and into evolving understandings of eugenics. As well as these broader conditions, he explained that Haldane's father was a biomedical scientist who believed in taking science out of the lab and using it to improve life in the real world. As Subramanian explained, Haldane was therefore accustomed to seeing science as a purposeful utilitarian experiment for practical and social use.

In Daedalus, Haldane points to the promise of science but also warns of the perils of its misuse. During the First World War, Haldane experienced the death of his comrades and the use of chemical warfare. In Daedalus, Haldane shares his anxieties about technology that could destroy society and advocates a secular morality for genetics, although he does not specify what this moral code should be. Subramanian said that 100 years on, issues of morality and the future of the human species loom ever more urgently.

Next to speak was Max Saunders, interdisciplinary professor of modern literature and culture at the University of Birmingham. Professor Saunders said that Daedalus represented a new way of thinking, of connecting science with social possibilities and transformations. Haldane was interested in what people will do next with technology, and was very good at imagining new possibilities that lie ahead.

Within the wide-ranging text of the Daedalus lecture – covering topics from science and medicine to poetry and religion – Haldane introduces the idea of ectogenesis (creating children outside the womb). Haldane sees ectogenesis as something that could liberate women, a biological invention giving rise to a new kind of freedom. For Haldane, Professor Saunders explained, it was important to free ourselves from outmoded thinking and to engage in thought experiments to imagine genuine change. How do we know if we want ectogenesis if we don't think around it and explore how it will affect work, parenthood and sex?

Nick Hopwood, professor of history of science and medicine at the University of Cambridge, then explained how Daedalus reframed research into development and reproduction from observation studies with no practical application to the creation of new organisms. At the time, reproductive science was in its infancy and fertilisation was only mentioned briefly in Daedalus. However, the discussion of reproduction outside the human body cleared a path to today's use of IVF.

Haldane knew the brothers Julian Huxley (biologist and avowed eugenicist) and Aldous Huxley (novelist), and the Daedalus lecture did much to inspire Aldous' famous novel Brave New World. Professor Hopwood said that besides inspiring this dystopian book, Daedalus also helped to focus research into artificial fertilisation and the creation of life. In the 1930s, researchers developed a line of IVF research that was reported at the time as 'the Haldane-Huxley fantasy made real'. Professor Hopwood explained how this drew attention to the research, making small steps seem significant, while also allowing researchers to reassure the public that they were not doing anything so extreme as described in the Huxley novel.

The final speaker was Dr Chloe Romanis, assistant professor in biolaw at Durham University. Dr Romanis said that ectogenesis has been used by scholars, from Haldane to more recent gender studies, as a provocation to think about what sort of future we want. This question has been made more pertinent by recent developments in partial ectogestation for use in neonatal care, although full-blown ectogenesis – as envisaged by Haldane – is still neither scientifically possible nor legally permissible in many jurisdictions.

Dr Romanis explained that discussions about who is allowed to be pregnant, and in what circumstances, play a big role in thinking about eugenics. She argued that Daedalus carries undertones of coercive uses of ectogestation, of assumptions about who are the right and wrong persons to reproduce, and she questioned whether such a concept can give rise to the reproductive liberty that Haldane speaks of. How can we ensure genuine choice? Dr Romanis said that while ectogestation can bring benefits, the extent to which it can provide reproductive choice is sometimes overstated, when what is needed more urgently is (for example) better maternity care.

The speakers were then asked a range of questions by audience members, including what the lessons of Daedalus for current researchers might be. Professor Hopwood said researchers need to think about the range of options, and to discuss the unintended as well as intended consequences of their research. Dr Romanis said speculation about reproductive futures is useful, while Subramanian said Daedalus serves as a reminder that a researcher's work does not only exist on their computer.

The speakers were also asked to comment on any connection between Haldane and the birth of the eugenics movement, and also the relevance of Daedalus today with the potential for heritable genome editing on the horizon. Subramanian and Professor Hopwood both observed that Haldane had an increasingly critical relationship with eugenics, while Professor Saunders said the Haldane went far further than most of his peers in criticising eugenic thinking during the interwar period.

On the advent of genome editing, Professor Hopwood said it was important not to draw connections with history too quickly, as today's thinking about reproductive technology takes place within very different circumstances. As Starr asked at the beginning of the event, is Daedalus' maze somewhere humanity is destined to stay lost, or do we – as Haldane suggested – have the wit to stay on top of and in control of our innovations?

PET is grateful to the Anne McLaren Memorial Trust Fund and Cambridge Reproduction for supporting this event.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.