If we had to choose a moment in history to represent the birth of IVF, what moment would we pick? The birth of Louise Brown in 1978? The conception of Louise Brown in 1977?

We might choose the first time Robert Edwards and Barry Bavister achieved IVF in human cells in the laboratory in 1968. Or their landmark paper with Patrick Steptoe the following year, describing this achievement and stating modestly that 'there may be certain clinical and scientific uses for human eggs fertilised by this procedure'.

Or we could go all the way back to Walter Heape, who in 1890 achieved the first live birth following embryo transfer in mammals (specifically rabbits). But we don't have to go quite as far back as that. A case can be made that IVF in humans – as an idea, if not a practical reality – was born 100 years ago, with a lecture in Cambridge entitled Daedalus, or Science and the Future.

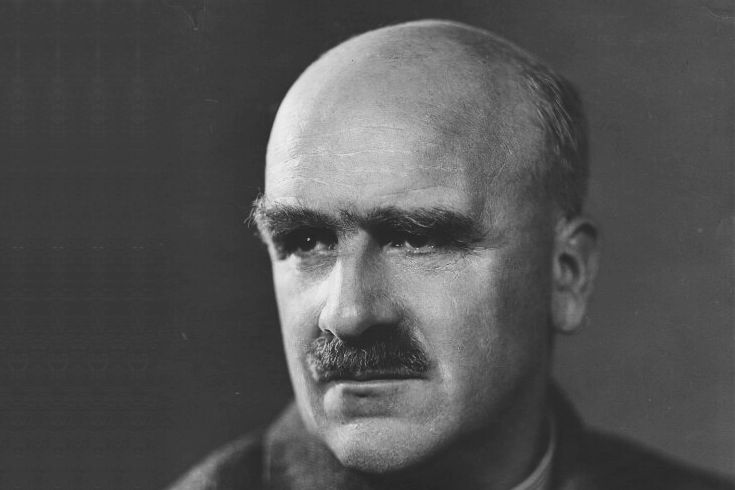

JBS Haldane (1892-1964) – geneticist, polymath and provocative public intellectual – used this lecture to argue that 'the biologist is the most romantic figure on Earth at the present day'. The lecture's title comes from his statement that while 'the chemical or physical inventor is always a Prometheus', it is a different figure from Greek mythology – Daedulus – who better embodies a new era of biomedical innovation.

Haldane was a dominant character, as the title (and genetics-themed pun) of a recent Haldane biography has it – a larger-than-life figure whose virtues and flaws alike ran to extremes. His Daedulus lecture is wide-ranging, covering all fields of science (and much else besides), and peppered with mischievous jokes. It also includes what can only be described as science fiction – a passage supposedly written 'by a rather stupid undergraduate' 150 years in the (then) future.

Haldane's imagination went far beyond IVF as we now know it. He used the lecture to coin the term 'ectogenesis', by which he meant moving the human reproductive cycle (including all of embryo/fetal development) out of the human body altogether. The science fiction section of his lecture imagines ectogenesis being achieved in humans in 1951, and then becoming a standard method of human reproduction by 1968.

Note that Haldane proposes this future after he has cautioned that within one generation, his lecture may come to seem 'modest, conservative, and unimaginative'. He would perhaps not be too impressed, then, that in the real world of 2023 full ectogenesis remains a distant prospect. But inroads have been made into the partial ectogenesis of animals, and also into human in vitro gametogenesis – that is, creating viable sperm and eggs in the laboratory.

Haldane's lecture so unsettled his friend Aldous Huxley, that it led Huxley to write the famous dystopian novel Brave New World, which continues to shape apprehensions about reproductive and genetic technology to this day. So familiar is this novel's title – which is lifted from Shakespeare, but Huxley is now more commonly associated with it – that one only has to say 'brave new world', and people understand the sort of unease that is being conveyed.

Meanwhile, Haldane's student Anne McLaren would go on to do pioneering work with mice in the 1950s that paved the way for IVF, in some sense helping to bring Haldane's imagination to life. McLaren also went on to pioneer the regulation of IVF in the 1980s as part of the Warnock Committee, thereby helping to reassure the public that some of the excesses of Haldane's vision would be moderated.

All of this would be reason enough to remember Haldane and Daedalus, but there's more. The Daedalus lecture became a milestone in public engagement with science when it was adapted by Haldane into a book later in 1923, becoming the first volume in the influential Today and Tomorrow (or as it was styled at the time 'To-day and To-morrow') series.

This series of books, which ran for 110 volumes from 1923-1931, sought to make controversial issues in science and technology accessible to the general public. The series included a rebuttal to Haldane's Daedalus by another Cambridge luminary, Bertrand Russell. The series also provoked responses from public figures ranging from Winston Churchill to Evelyn Waugh.

When the series was launched, the following blurb was used to promote it. 'In every department of knowledge new discoveries are constantly being made, and novel theories of the utmost importance put forward. Too often these contributions are lost in the files of learned journals and in other inaccessible places. Yet many of them cannot fail to be of the greatest interest to the public. It will be the object of this little series to make such papers available in a handy format.'

A century on, the language may have changed slightly, but this mission statement is not too far removed from what PET seeks to do with its public events and with BioNews. We take developments in science, medicine, policy and ethics that 'cannot fail to be of the greatest interest to the public', and we make them more accessible and comprehensible 'in a handy format'.

For all of these reasons, PET is delighted to be holding a free-to-attend online event entitled '100 Years of Daedalus: The Birth of Assisted Reproductive Technology', exploring Haldane's legacy while also considering the future of assisted reproduction. The event will be held on Wednesday 1 February, 100 years (almost to the day) after Haldane gave his original Daedalus lecture.

Given the centrality of Cambridge to the events outlined above, and the role played by Haldane's student Anne McLaren, it is particularly fitting that this event has been generously supported by the Anne McLaren Memorial Trust Fund and Cambridge Reproduction.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.