A mutated protein associated with Alzheimer's disease may trigger the death of brain cells known to be vulnerable in frontotemporal dementia.

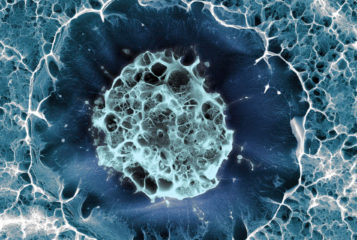

Frontotemporal dementia is a devastating disease that affects the front and side (temporal) areas of the brain, leading to severe behavioural changes and cognitive impairment. In an attempt to better understand its pathology, US researchers created cerebral organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs) to mimic and study the early growth and development of the cerebral cortex.

'IPSCs are powerful tools. They allow researchers to study each patient's personalised disease in a Petri dish,' said senior author Dr Sally Temple, scientific director of the Neural Stem Cell Institute in Rensselaer, New York. 'In this study we were able to get a better look at what might be going on in a patient's brain at early stages of disease development, even before symptoms emerge.'

The organoids were derived from the stem cells of three patients, all of whom carried a specific mutation in the sequence of the tau protein. This variant, called V337M is a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias.

The study, published in Cell, showed that after six months the mutant organoids presented fewer excitatory neurons than those derived from the healthy control cells, demonstrating that the tau mutation causes higher levels of cell death of this specific class of neurons. Excitatory neurons are usually activated by glutamate, a common neurotransmitter in the brain, and are known to be susceptible in frontotemporal dementia. The mutant organoids also presented with higher levels of harmful versions of tau protein and high levels of inflammation.

'Excitatory neuron cell death, tau protein deposits, and inflammation are classic hallmarks of the kind of damage seen in many forms of frontotemporal dementia,' said first author Dr Kathryn Bowles, from the Ronald M. Loeb Centre for Alzheimer's Disease in New York. 'What we wanted to know next was: what are the cellular and molecular processes that occur before the appearance of these disease hallmarks?'

To answer this question, researchers examined two- and four-month-old organoids. They found that several molecular processes are impaired during the early stages of organoid development, including the response to cellular stress and autophagy, or the degradation and recycling of damaged cellular components. Further experiments confirmed that the V337M mutant tau triggers the release of toxic levels of glutamate that can overstimulate excitatory neurons putting them under great stress and significantly reducing their lifespan.

Interestingly, researchers identified an experimental drug, apilimod, that could prevent the death of these neurons. Originally designed to tackle Crohn's disease and several viral infections, apilimod is able to alter a cell's protein recycling system, thereby stabilising the levels of glutamate in the cell and preventing glutamate-induced neuronal death.

The study provides new insights into how cerebral organoids can be powerful tools that, according to Dr Alison Goate, director of the Ronald M. Loeb Centre and a senior author of the study, can help us to 'model and learn to understand the causes of dementia' and eventually 'develop effective treatments for frontotemporal dementia and other heart-wrenching neurodegenerative disorders.'

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.