Once considered a topic of science fiction, genome editing has rapidly progressed to the forefront of academic discourse, forcing us to confront the ethical implications of its use at both a personal and societal level. The Francis Crick Institute, situated in central London, is currently hosting the Cut + Paste exhibition until 2 December 2023 – an immersive experience which is curated to make us question how we define acceptable forms of genetic alteration.

My initial thought as I entered the exhibition space was the befitting nature of the event's tagline: 'Discovering the building blocks of life'. The area is subdivided into four sections, complete with giant plush dice; a plethora of colourful objects and giant ping-pong balls. In short, the space resembles an interactive creche for young scientific minds or a post-modern nightclub in Shoreditch. Although the layout is inviting and reminds me of the importance of events which inspire the next generation of scientists, the child-like appeal almost masks the true depth of the exhibit.

In the 'Pass it Down' zone, you are invited to consider genetic inheritance – which of your tastes, traits and talents you'd like passed on to the next generation. By arranging props on a magnetised board (eg, a furry paw for 'animal lover'), attendees can make their selections and post to social media. Although this appears rather superficial, further information is provided, which reviews current limitations of genome editing techniques. This covers the illegality of hereditary genome editing in the UK and the inability to prevent health conditions caused by multiple gene variants, such as heart disease and diabetes.

The event is fantastic in its ability to engage all demographics, regardless of the individual's age or scientific background. Younger children can revel in the joys of a magnetic lollipop, whereas older generations can debate if genome editing should be used to prevent environmental disasters.

Scattered around the exhibition are deceptively simple questions – some of which seem relatively innocuous until you really consider your response. For instance, one sign asks, 'If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be?' Many visitors may flippantly say they'd like to be slightly taller or have a more even skin tone. But why do we consider these characteristics desirable? They may be subtle indicators of genetic fitness or solely represent ideals deemed favourable by social conditioning. However, can either of these explanations justify genetically unifying an entire population? As proposed in a nearby quote from Corinne Othenin-Girard, PhD student in Sociology, Switzerland: 'Would using genome editing technology to create the "perfect" or "ideal" human risk making us become less tolerant of 'imperfections'?'

There are obvious medical applications for CRISPR genome editing in treating conditions such as cystic fibrosis or sickle cell disease. However, Cut + Paste prompts us to define what is considered 'undesirable' and asks who should make that decision from a regulatory standpoint. It was reassuring to come across opinions from those actually affected by disabilities. Rebecca Cokley, first disability rights programme officer at the Ford Foundation, New York, was quoted as saying 'Many of us see our disabilities as a rich and diverse culture, many of us want to pass that culture down to our children through our genes, and many of us see no reason not to.' This diversity of opinion was rather enlightening and underpins the complexity of considering genetic engineering as an all-purpose therapy.

The 'Roll the Dice' activity was a highlight of the event, where you are randomly assigned a question based on a dice throw and encouraged to state your opinion through an interactive ball game. After rolling the giant dice, which made this 6'3 man feel like a Borrower, I was asked 'Should scientists edit plant genomes to help humans have better health?'. At first glance, this may seem an easy decision. As the accompanying information book described, genetic alteration could lead to more nutritious and disease-resistant crops, capable of dealing with overpopulation and increasing lifespans. However, this is an emergent technology with unknown ecological consequences, and we may instead consider the promotion of responsible farming practices and diet diversity.

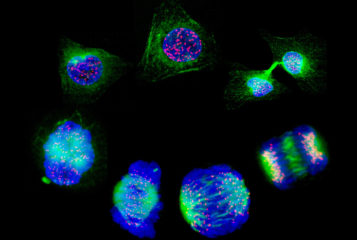

Although Cut + Paste may initially present as an assault of primary colours and glamourised photos of DNA sequencing gels, the exhibit contains remarkable depth if you care to look for it and will leave visitors curious about the future of genome editing.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.