In June 2023, Anke Wesenbeek (co-author), a 30-year-old Belgian donor-conceived woman won a landmark court case after a year-long battle to gain information about her paternal heritage.

Two years before, after extensive research through commercial DNA-testing companies, she identified a man as her probable genetic father, but a direct DNA-comparison was needed for absolute certainty. The man was offered professional mediation and support by the Flemish Ancestry Centre, but their correspondence went unanswered. When Wesenbeek engaged a lawyer to send similar offers, the man's lawyer formally confirmed his client's unwillingness to cooperate. Wesenbeek therefore decided to take her quest to court.

Belgium is one of the few remaining European countries to still operate an anonymous donation policy. It wasn't until 2007 that the traditional preference for donor anonymity was enforced by law. The 'Law on Medically Assisted Reproduction' (MAR) followed the parliamentary committee's view that sharing any donor information must be avoided as this could reinforce the 'myth' that the donor's genes determine the donor offspring's characteristics (Nys & Wuyts, 2007). In 2012, advocacy by donor-conceived people reopened the discussion, leading to law proposals to abolish donor anonymity, but no parliamentary majority has been achieved.

Counterproposals suggest a multiple-track system that allows prospective parents to choose between anonymous, known and identity-release donor options. This aligns with the official advice from the Belgian Advisory Committee on Bioethics that takes the parental and donor autonomy as their basic principle and explicitly refutes the rights of donor-conceived people to know their genetic background citing the utilitarian argument that any harm to their welfare is insufficiently supported by empirical evidence.

It is against this legal stalemate that this court ruling is so important. The judge ruled that the man must undergo a paternity test to verify a presumption of genetic fatherhood substantiated by genetic genealogical research. Both parties had called upon Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, the right to privacy. Wesenbeek argued that she had the right to know her genetic background as a fundamental part of her identity. The defendant justified his refusal to comply by relying on his right to privacy and physical integrity, but also on the 2007 MAR Law that protects donor anonymity (even though that post-dated Wesenbeek's conception).

The judge considered the MAR Law to be irrelevant because it protects against legal claims by offspring regarding property or family relations but does not explicitly prohibit donor-conceived people knowing the donor's identity. In this case, Wesenbeek only sought definitive genetic information, not any other legal recognition. Moreover, the donor's anonymity was considered to be part of an agreement between the clinic, the donor, and Wesenbeek's parents, in which she had no part and for which she could not be held accountable.

The judge ruled in favour of Wesenbeek, based on her personal testimony, but also taking into consideration a wide variety of other sources. These included: international jurisprudence; international movements towards greater recognition for the rights of donor-conceived people through abolition of donor anonymity; the contestation of the Belgian Law on MAR within legal literature from a children's and adults' human rights perspective; the 2019 Council of Europe recommendation that all member states should waive donor anonymity, and the fact that commercial DNA-testing has rendered donor anonymity illusive.

In contrast, the judge considered the requested DNA-test to be only a limited breach of the defendant's privacy (because his DNA would only be used to confirm Wesenbeek's genetic origins) and a negligible threat to his physical integrity (as the DNA-test would only require a painless cheek swab).

The significance of this ruling for Belgium and more widely is plain. It is the first time that the human right of a Belgian donor-conceived person to ancestral information has been acknowledged in court. This puts additional pressure on Belgian politicians to finally adopt a much-needed law that unequivocally protects this right.

For other jurisdictions that have signed up to the European Convention on Human Rights, it opens the door to further challenges to laws allowing donor anonymity. Additionally, it demonstrates the power of using legal routes to get the human rights of donor-conceived people acknowledged. Finally, the fact that this ruling retroactively overrides the previously agreed anonymity of a sperm donor, shows that the recognition of human rights cannot be made conditional on historic practices and agreements.

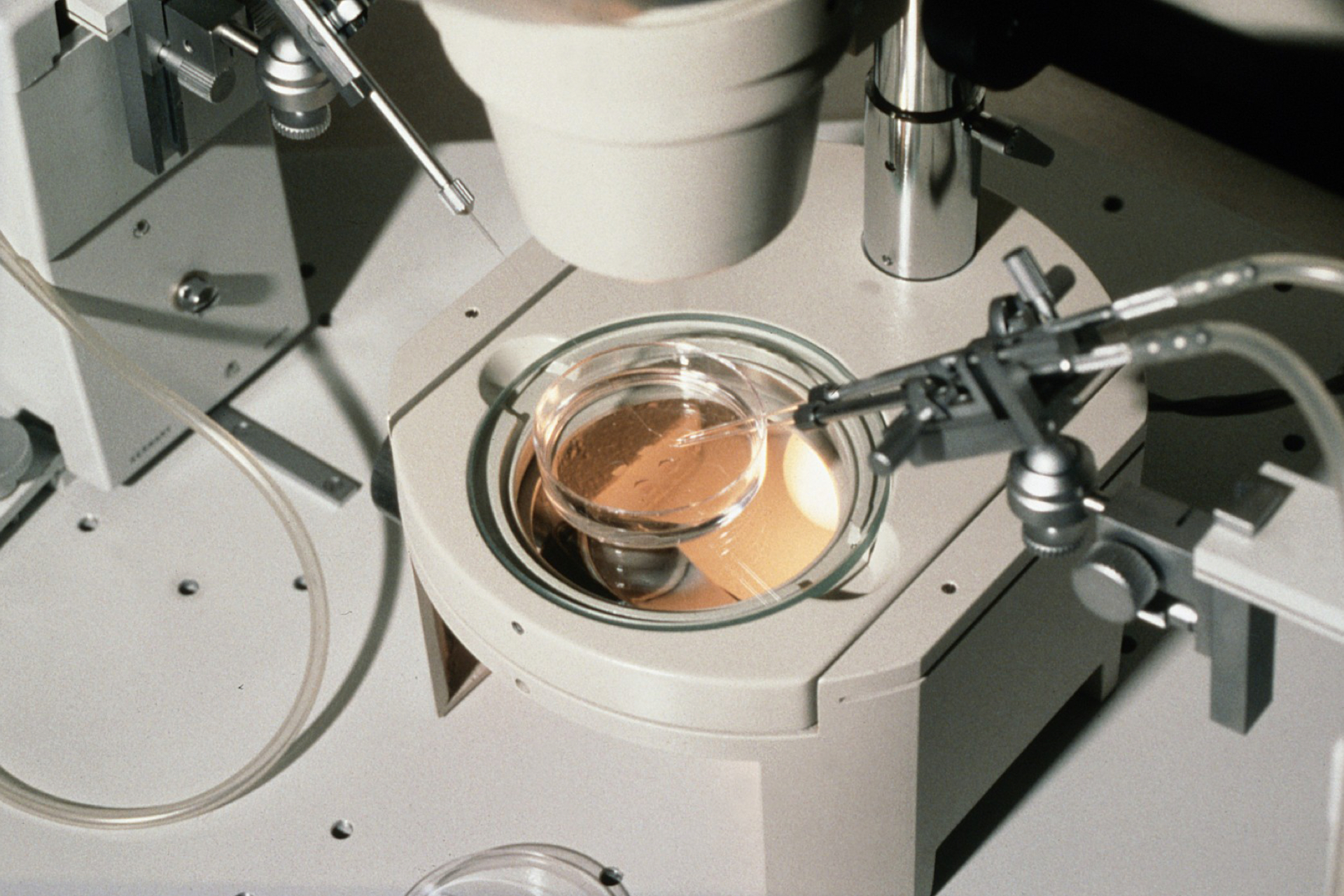

The emergence of commercial DNA-testing companies is enabling many donor-conceived people to identify their unknown genetic parent, but this is not enough by itself to reliably meet the needs of all. It can be time-consuming, complex, and emotionally draining and there is no guarantee of success. When a probable genetic parent is identified who then refuses to take a confirmatory DNA-test, as in this case, this causes additional distress. Of course, being identified through this route can also be challenging for (presumed) donors.

Although victorious from a human rights perspective, this case is a reminder of the multi-faceted long-term personal impact of donor conception treatments on all parties. It illustrates the need for better education of donors, recipient parents and health professionals, in which the genetic tie between donors and offspring is recognised as an enduring connection between human beings (a framing that has been found lacking in Belgium ). It highlights the need for statutory donor registries, and free professional support services for parties seeking or receiving information about each other.

No donor-conceived person should ever need to go through stressful and costly court battles to get the justice and care they deserve.

The authors wish to thank Dr Marilyn Crawshaw from the University of York for her help and advice with this commentary.

Sources and References

-

Accessing origins information: the implications of direct-to-consumer genetic testing for donor-conceived people and formal regulation in the United Kingdom by Adams, D. Crawshaw, M., Gilman, L., & Frith, L.

-

De wet betreffende de medisch begeleide voortplanting by Nys, H., & Wuyts, T.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.