Professor He Jiankui, the Chinese scientist who created the world's first genome-edited babies, has been sentenced to three years in prison for violating medical regulations.

According to the state news agency Xinhua, the court in Shenzhen, China, found Professor He guilty of illegal medical practices, fining him 3 million yuan (£327,360) in addition to the sentence. Last year, Professor He shocked the scientific community following his claim that he had edited the genomes of embryos which resulted in the birth of twin girls (see BioNews 977).

Two other members of Professor He's research team, Zhang Renli and Qin Jinzhou, received lesser fines and sentences. All three pleaded guilty in a private trial and face a lifelong ban on engaging in assisted reproductive services.

'The three accused did not have the proper certification to practise medicine, and in seeking fame and wealth, deliberately violated national regulations in scientific research and medical treatment,' the court said, according to Xinhua. 'They've crossed the bottom line of ethics in scientific research and medical ethics.'

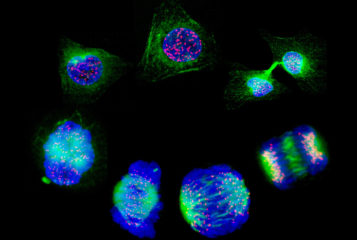

To infect cells, the HIV virus attaches to the protein encoded by the CCR5 gene. A small number of people are less susceptible to HIV due to having a natural mutation in CCR5 that prevents the virus from attaching to the CCR5 protein. In his announcement at a conference in Hong Kong in 2018, Professor He claimed he had used CRISPR/Cas9 which can edit specific parts of the genome, to recreate the mutation in human embryos.

However, the court found Professor He had forged documents from an ethics review panel to recruit couples where the male partner was HIV-positive and the female partner HIV-negative for the experiments. Couples were offered funded IVF in return for taking part.

Molecular biologist Professor Fyodor Urnov, at the Innovative Genomics Institute, University of California, Berkeley, told MIT Technology Review that Professor He's claim to have made the CCR5 mutation was 'a deliberate falsehood', and that instead new mutations were created in the gene as well as elsewhere in the genome. The consequences of these off-target mutations are not yet known.

Professor Robin Lovell-Badge, Group Leader at the Francis Crick Institute in London said: 'It is far too premature for anyone to attempt clinical application of germline genome editing; indeed, at this stage we do not know if the methods will ever be sufficiently safe and efficient – although the relevant science is progressing rapidly, and new methods can look promising. It is also important to have standards established, including detailed regulatory pathways, and appropriate means of governance.'

'These aspects are being looked at by the Academies' Commission and by a WHO Committee, both due to report in 2020,' added Professor Lovell-Badge.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.