Thirty years on from the first birth resulting from intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), PET's recent discussion event '30 years of ICSI: An Injection of Hope for Male Infertility' invited a panel of experts to discuss the past, present, and future of the technique.

PET's director, Sarah Norcross chaired the event. She began by explaining how after the first IVF baby was born in 1978, poor IVF success rates came to be associated – in part – with infertility that was partially or wholly attributable to the male in a couple, otherwise known as male-factor infertility.

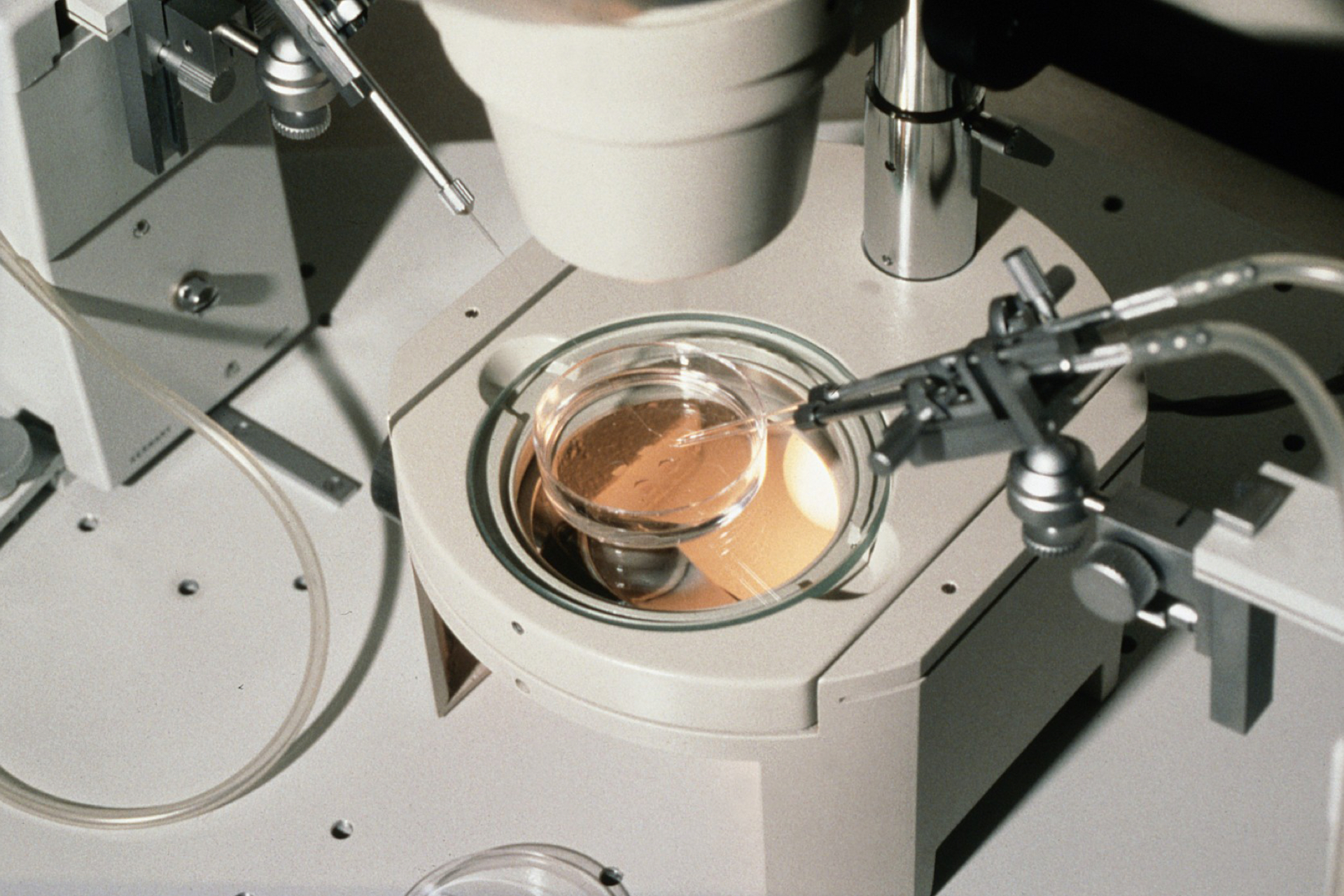

A solution came 15 years later with the invention of ICSI which, instead of mimicking natural conception by surrounding an egg cell with sperm sperm cells in a dish (conventional IVF), uses a tiny needle to inject a single sperm into the egg's interior. ICSI has helped millions of couples worldwide to conceive.

The first speaker was ICSI pioneer André Van Steirteghem, now emeritus professor at the Free University of Brussels (VUB), who described how his team developed ICSI while trying to perfect a different technique (see BioNews 1162). In the mid-80s Professor Van Steirteghem's group accidentally found that, in contrast to earlier research in mice, normal fertilisation and embryo development in humans occurred when sperm is inserted into the egg's cytoplasm.

Following the first birth of an ICSI-conceived child in 1992, the technique's use in patients with severe male-factor infertility resulted in success rates similar to conventional IVF, and offered an alternative for couples who otherwise would have had little option but to use donor sperm.

Professor Van Steirteghem explained how ICSI offers an advantage when performing pre-implantation genetic testing. While sperm remains or cumulus cells are often the cause of contamination during conventional IVF, ICSI reduces the chance of contamination when performing an embryo biopsy.

Key to the advances made since ICSI was established is the way the research team in Brussels shared their work with peers, which was somewhat unusual at the time (and is even more unusual now), highlighting the importance of collaboration in research.

The second speaker was Dr Morven Dean, a trainee clinical embryologist at the Assisted Conception Unit in Dundee's Ninewells Hospital, who talked about the use of ICSI in current clinical practice. She outlined scenarios where there is strong evidence justifying the use of ICSI: severe male-factor infertility when patients present low sperm quality and motility, as well as to fertilise cryopreserved or in vitro matured oocytes, and to prevent contamination during pre-implantation genetic testing. In patients with only mild male-factor infertility, the evidence for using ICSI is mixed.

However, Dr Dean showed figures indicating that globally ICSI is used more than conventional IVF: two-thirds of assisted reproduction cases worldwide used ICSI in 2011. Often these are cases for which little to no evidence exists for ICSI being superior, such as for couples with unexplained infertility, advanced maternal age or low oocyte yield, or even for no particular reason.

Dr Dean also explained that ICSI's overuse might be linked to clinicians' fear of total fertilisation failure – when none of the eggs retrieved in a cycle successfully form an embryo – for which the risks seem to be lower when using ICSI (two percent vs five percent in standard IVF).

The future challenges of ICSI were further discussed by Professor Christopher Barratt, who is head of Reproductive Medicine at the University of Dundee. He highlighted many basic questions in the field of male reproductive health, like what is causing the decline in sperm count (see BioNews 911), which remain to be addressed.

Robust diagnostic tests to measure the incidence of male infertility are still needed, and there is also a lack of consensus on how to detect sperm damage. Taking the example from the collaborative approach which enabled the fast vaccine roll-out during the global pandemic, Professor Barratt highlighted the need for more large-scale studies to answer these important questions. He also introduced promising initiatives which aim to collect high-quality data on a global scale to measure, for example, the significant gap in research funding spent for reproductive health.

The final speaker, Professor Barbara Luke, from the Department of Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Reproductive Biology at Michigan State University, presented her work on the largest population-based study in IVF children in the United States. This research suggested an increased risk in birth defects and childhood cancer following conception using ICSI. Whereas male-factor infertility has remained stable in the past two decades, the use of ICSI has increased approximately ten percent.

By comparing more than 165,000 IVF-conceived children with over 1.3 million naturally conceived children born across four American states, Professor Luke and her colleagues found that the overall rate of cancer was higher in IVF children. Furthermore, ICSI, in combination with male-factor infertility, led to an increased risk of non-chromosomal, blastogenic, cardiovascular and genital-urinary defects after birth. She listed epigenetic changes, freeze-thawing of embryos and subfertility factors as some possible causes.

Chairing the Q&A panel discussion, Norcross, introduced medical genetics professor Inge Liebaers from the Free University of Brussels (VUB), who is an expert on preimplantation biomarkers and diagnosis. Being asked to briefly comment on Professor Luke's study, she reiterated the hurdles of studying several factors in these prospective studies, to understand if and how assisted conception negatively impacts later life.

The first question asked by an attendee was whether advising men with fertility issues to adopt a healthier lifestyle and diet could improve sperm quality. While agreeing that such changes might have a positive impact, at least up to a point, the speakers argued that more support is needed in IVF clinics to help patients make these changes.

Queried about a potential link between the overuse of ICSI and the rise of autism spectrum disorders among children, the panel agreed that not enough is known at present, and that more funding is required to conduct follow-up studies.

Professor Luke observed that fertility treatments are continuously changing, which makes it difficult to answer the question of whether the underlying conditions in infertile couples could predispose future children to diseases such as cancer.

Dr Dean was asked how to incentivise laboratory managers to offer the most appropriate IVF procedure, regardless of the increased financial benefit to the clinic of using procedures such as ICSI. She reiterated that the habit of using ICSI as a safety blanket in IVF clinics, due to fear for treatment failure, could be overcome by conducting more clinical trials and rebuilding trust in conventional IVF. Furthermore, the panel discussed the importance of communication between clinicians and embryologists, when it comes to explaining the success or failure of treatment.

During the final part of the Q&A, the panel discussed the need to find better ways to explain risk to patients, perhaps via more counselling. Finally, after Professor Van Steirteghem warned the panel about the increasing domination of financial interests in the medical world, Professor Barratt concluded that more consistent collaboration and research funding is the only way forward.

Overall, the story of ICSI teaches us a great lesson about the importance of openness and collaboration in advancing assisted reproduction. Only more diligent research and practice will tell when, and for whom, ICSI is appropriate.

PET is grateful to the Scottish Government for supporting this event.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.