On 14 January 2022 it was the 30th anniversary of the first birth after intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) at Brussels University Hospital. During the 38th Annual Meeting of European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (Milan, Italy 3-6 July 2022) a special symposium was held on this topic. I lectured on this topic on behalf of Neelke De Munck, Herman Tournaye and all colleagues of BrusselsIVF (UZBrussel) and Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

BrusselsIVF was, along with Vrije Universiteit Brussel, the site of both the treatment and research which allowed this birth to take place, to a couple who had experienced male-factor infertility. It was of course, not the last birth to take place using the technique, with four more to follow shortly after, and it is now used routinely the world over.

Inventing ICSI

At the end of the 1980s it become obvious that conventional IVF was a good solution for couples with female factor infertility, but not for couples where the sperm count was too low. The remaining solution for these couples was to use artificial insemination with donor sperm. Several groups asked the question how we could better assist the fertilisation process when male infertility was preventing conception.

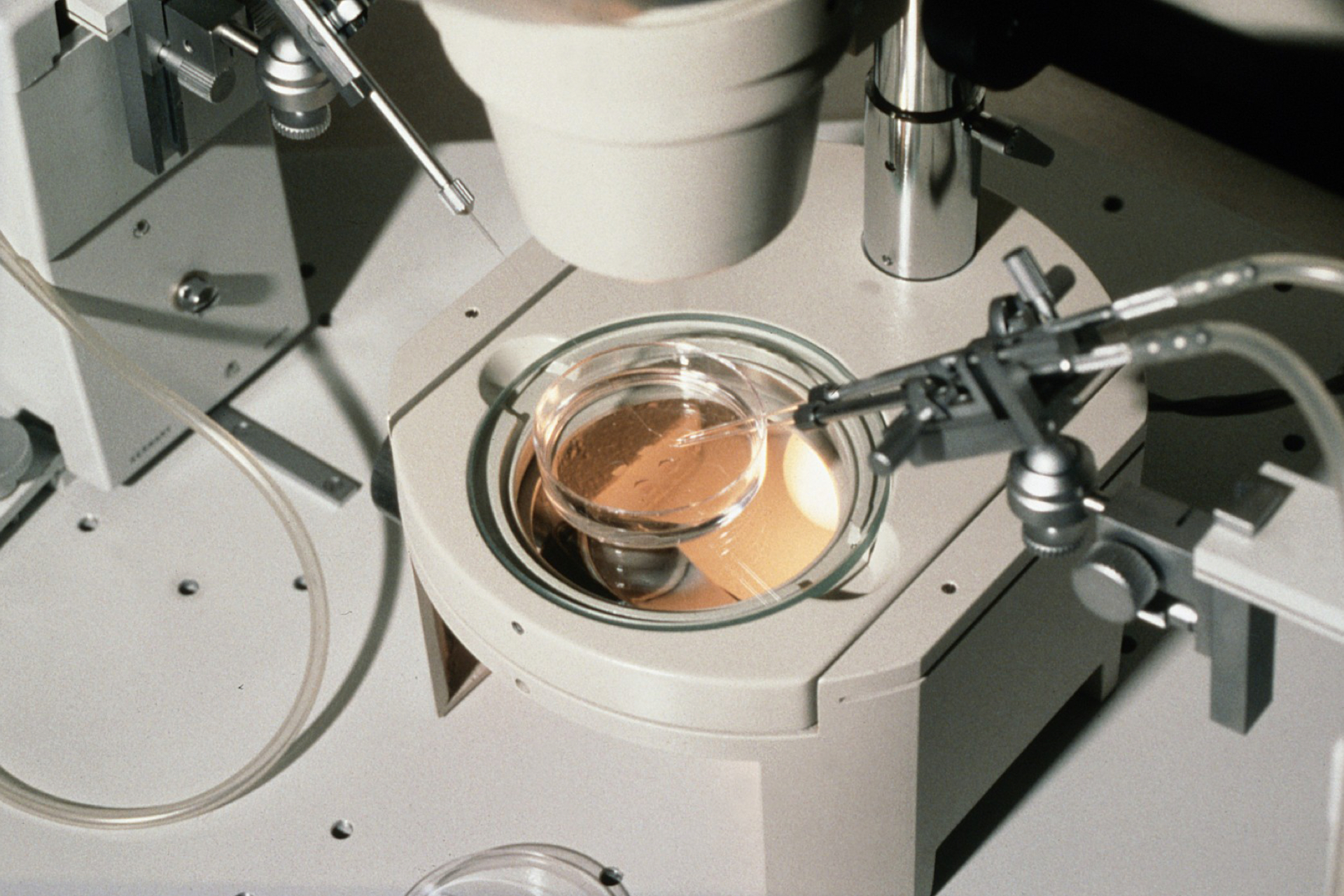

Micromanipulation procedures were introduced: The two initial assisted fertilisation procedures: zona drilling and partial zona dissection were not successful in humans. Around that time a few case reports were published on another assisted fertilisation procedure: subzonal insemination (SUZI) involving the insertion of a few spermatozoa between the zona pellucida and the membrane of the oocyte, helping it to enter the egg. We decided to explore the scope of this approach for assisted fertilisation at BrusselsIVF.

Thanks to a grant from the Fund for Scientific Research – Flanders we investigated in mice whether the enhancement of the acrosome reaction (which is when the sperm cell releases enzymes necessary to enter the egg) of mouse sperm resulted in fertilisation and embryo development after a single 'treated' sperm was injected subzonally, underneath the outer protein layer of the egg. Our hypothesis proved to be correct: good rates of fertilisation and embryo development occurred, many normal pups were born and they were able to reproduce.

These experimental results led us to consider introduction of SUZI into the clinic for patients that had failed several cycles of conventional IVF. Ethical approval was asked for and obtained from the VUB Hospital Ethical Committee under the condition that all pregnancies and children born would be part of a thorough follow-up programme. Patients were fully informed and agreed to the follow-up programme including a prenatal diagnosis.

Clinical SUZI was started and a number of pregnancies and births occurred following use of the procedure. The technical procedure is delicate and sometimes one of the sperm entered into the cytoplasm of the oocyte. We noticed that this 'failed SUZI' led to normal fertilisation and initial embryo development. In cases where the only available embryo was after 'failed SUZI', it was transferred. We called this procedure ICSI.

The first ICSI child was born on 14 January 1992, following the transfer of a single 'failed SUZI' embryo, created after fertilisation failed on 11 other oocytes from the couple. In the following period, we were able to demonstrate that ICSI was more efficient than SUZI and from July 1992 we only applied ICSI in patients in need of assisted fertilisation.

We deliberately choose to share our experience widely with our peers and thereafter ICSI was performed in many centres worldwide and ICSI has been mushrooming.

The proportion of IVF cycles that use ICSI varies significantly by region, being much more common in the USA than it is in Europe, for example. Around 70 percent of all IVF cycles globally use ICSI, suggesting it is widely used for non-male factor infertility. Failure of previous IVF cycles is often the reason for using ICSI. Many patients prefer to use ICSI in countries where only a limited number of cycles are reimbursed by social security or where no reimbursement is in place as success rates are perceived to be higher than conventional IVF rates.

ICSI proved to treat infertility in couples with severely impaired sperm, including cryptozoospermia. For these patients, ICSI results were similar to conventional IVF treatment for patients without male factor infertility. ICSI using sperm that had been surgically removed from the epididymis or testes could also solve the problem in patients with obstructive azoospermia. Patients with non-obstructive azoospermia can also be helped if sperm cells can be found by testicular sperm extraction but the chance to have a child in couples where the male partner has non-obstructive azoospermia is low. However, most of these couples will embark on treatment even after full counselling before considering the use of donor sperm.

At BrusselsIVF, ICSI is also used on in vitro matured oocytes following culture of immature oocytes with the cells that surround it collected from antral follicles in polycystic ovary syndrome patients. For couples undergoing PGT with biopsy of day three cleaving embryos or day five or day six blastocysts, ICSI is still the preferred procedure in order to avoid contamination at the time of biopsy by remnants of sperm or remnants of the cells from around the oocyte, which can occur when conventional IVF is used.

From the start in 1980 we have invested in clinical, translational and fundamental research. Now, this research is carried out by more than 250 individuals from BrusselsIVF, the centre for reproductive medicine of the UZBrussel and different research units at the VUB.

Professor André Van Steirteghem will be speaking at the free-to-attend online PET event '30 Years of ICSI: An Injection of Hope for Male Infertility', on Wednesday 2 November 2022.

Find out more and register here (scroll down and click/tap on the event title).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.