Mouse heart cells, genetically modified after a heart attack, recovered from the damage caused.

Scientists at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Centre (UTSW) used 'base editing' to change a particular gene that is overactive during a heart attack and responsible for much of the damage caused. In the weeks and months after the induced heart attack, the cardiac function of the mice was nearly indistinguishable from before their heart attacks.

'Rather than targeting a genetic mutation, we essentially modified a normal gene to make sure it wouldn't become harmfully overactive. It's a new way of using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing,' said Professor Rhonda Bassel-Duby who co-led the research.

The overactivation of a gene called CaMKIIδ is known to cause much of the damage from a heart attack by a mechanism that involves the oxidation of two methionine amino acids that form part of the CaMKIIδ protein.

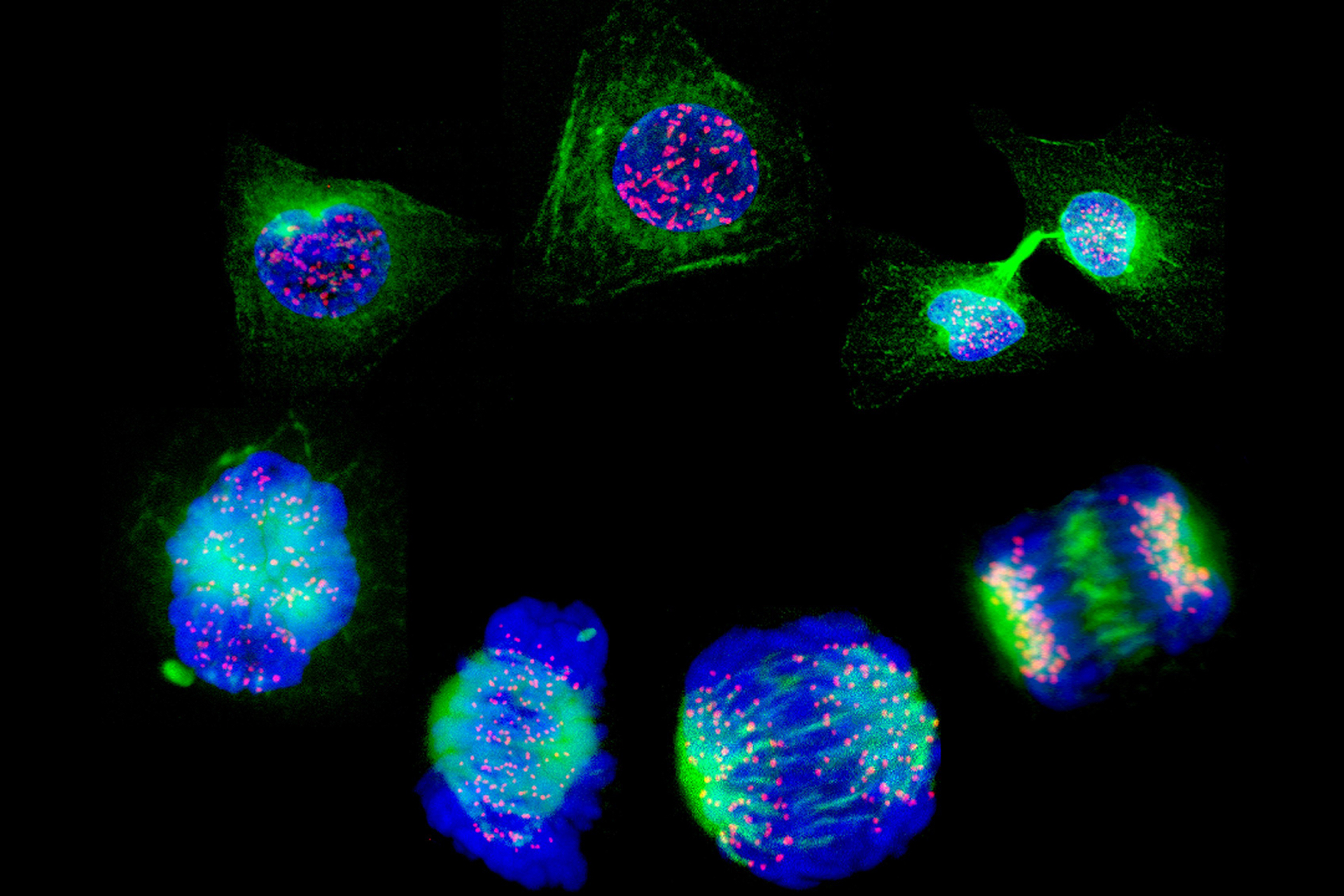

Publishing their results in Science, the scientists used base-editing to remove the oxidative activation sites of CaMKIIδ in human heart cells grown in the lab. Placing these cells in a low-oxygen chamber, which mimics the conditions of a heart attack, resulted in the cells recovering from damage and surviving. In contrast, non-edited heart cells showed many markers of damage and died.

Furthering their research, the scientists conducted the experiment using mice, who had their blood flow restricted to induce a heart attack. After 45 minutes the scientists used the base-editing technique directly on the animals' hearts. The edited and non-edited mice both had severely compromised heart function in the first 24 hours after their heart attacks. However, the genome-edited mice recovered, whereas the non-edited mice worsened over time.

'Usually, depriving the heart of oxygen for an extended period, as often happens in a heart attack, will damage it substantially. But those animals whose heart muscles were subjected to gene editing after induced heart attacks seem to be essentially normal in the weeks and months afterward,' said Professor Eric Olson, chair of molecular biology at UTSW, who co-led the study.

Furthermore, no negative side effects were observed a year after treatment and the scientists noted that the CaMKIIδ gene was not altered in any other organs.

Genome editing is most often discussed in relation to correcting genetic mutations that cause disease. However, this potential cardioprotective strategy is proposed to treat cardiovascular disease which is not caused by genetic mutations. Cardiovascular disease accounts for approximately 32 percent of all deaths around the world.

'What this shows is that if you can manipulate the body's response to injury, you could potentially avoid what we used to think was unavoidable (damage),' Dr Richard Wright, a cardiologist at Providence Saint John's Health Centre in California, who was not involved in the study, explained to MedicalNewsToday. '… if this new gene therapy works, it would be a game changer.'

However, the authors do caution that this treatment will need safety and efficacy studies before the therapy can be trialled in humans.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.