Removing additional chromosomes, or arms of chromosomes, can stop cancer cells' ability to form tumours.

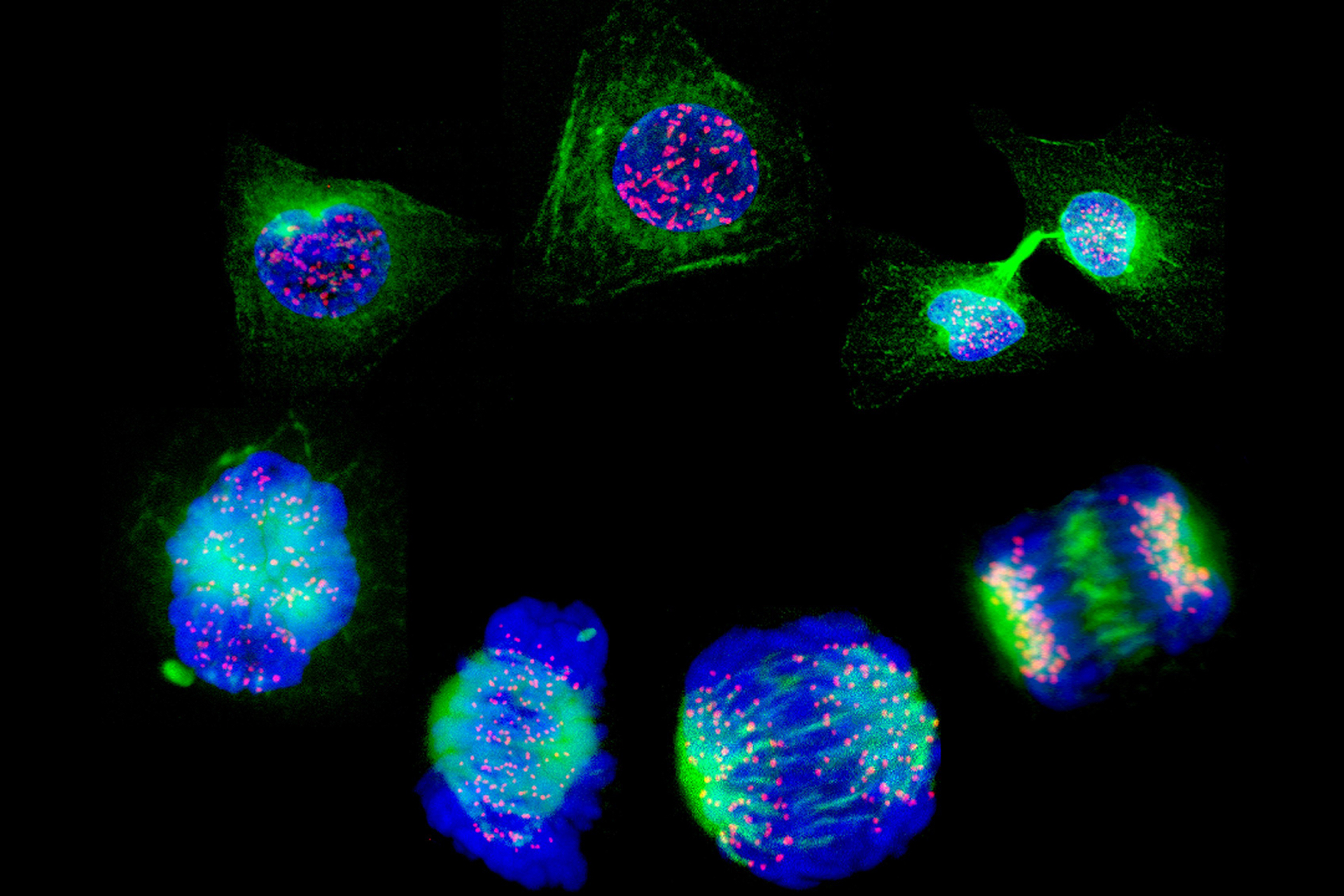

It has long been known that cancer cells are aneuploid, meaning they carry an abnormal number of chromosomes or replicated arms on their chromosomes. Using genome editing to remove these, scientists have found cancer cells can be stopped from forming tumours.

'If you look at normal skin or normal lung tissue, for example, 99.9 percent of the cells will have the right number of chromosomes, but we've known for over 100 years that nearly all cancers are aneuploid.' said Dr Jason Sheltzer, assistant professor of oncology surgery and of genetics at Yale School of Medicine, Connecticut, and senior author of a study published in Science.

The approach used by his team, known as Restoring Disomy in Aneuploid cells using CRISPR Targeting (ReDACT), is based on CRISPR genome editing which can target and edit specific regions of the genome. The research group focused on replication of a single arm of chromosome 1 in cancer cells from ovarian cancer, gastric cancer and melanoma cell lines.

Mice injected with aneuploid cells which had the replication, grew large tumours even in the presence of cancer drugs, but this was not the case when they were injected with the CRISPR-modified cells. This highlighted that the chromosomal abnormalities in cancer cells drive tumour growth.

To target the additional 'arm' of the chromosome, a gene from the common herpes virus was inserted into it in aneuploid cancer cells. Using a herpes treatment called ganciclovir, the extra chromosomes were then eliminated.

Cancer cells with the additional arm on chromosome 1 benefit from the existence of multiple copies of the gene MDM4, which negatively regulates activity of tumour-suppressing gene p53. Once the additional arm was removed, rapid growth of tumours was inhibited.

In CRISPR-edited cells, MDM4 expression was comparable to healthy cells without chromosomal anomalies and p53 activity was restored.

'This told us that aneuploidy can potentially function as a therapeutic target for cancer, almost all cancers are aneuploid, so if you have some way of selectively targeting those aneuploid cells, that could, theoretically, be a good way to target cancer while having minimal effect on normal, non-cancerous tissue.' said Dr Sheltzer.

So far, this approach remains an experimental tool and more research is needed before it can be assessed in clinical trials. However, the group from Yale is looking to investigate their findings in animal models and aims to use different cancer drugs.

Sources and References

-

Eliminating extra chromosomes in cancer cells prevents tumor growth

-

Oncogene-like addiction to aneuploidy in human cancers

-

CRISPR helps solve 100-year mystery of why cancer cells have extra chromosomes

-

Extra chromosomes - Long a mystery in tumors - may help them grow

-

Gene editing helped crack a 100-year-old mystery about cancer

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.