Do you remember those heady days of late-night dorm room discussions? Where, armed with a beverage of choice, you sought to grasp the ever-elusive meaning of life, what it meant to be human, whether the Matrix was real, and if it were, would it matter? If you do remember, then you'll certainly recognise the exciting jumble of thoughts Dr Philip Ball's 2022 Wilkins-Bernal-Medawar Medal lecture awoke in me.

The Wilkins-Bernal-Medawar Medal is an annual Royal Society prize, rewarding achievement in the areas of history, philosophy or social function of science. In 2022 this prize was awarded to Dr Philip Ball, former Nature journal editor and regular freelance writer for the Guardian and New Statesman. This article reviews the public prize lecture Dr Ball delivered when receiving the award, choosing to speak of the historical, ethical and social lens through which human genome editing can be viewed.

No stranger to the inverted pyramid of journalism, Dr Ball opens with his takeaway message, calling for science communicators to be more than translators, but also 'interpreters and contextualisers' of science. And nowhere is this more relevant than the constantly evolving field of genome editing.

Over the course of an hour, he takes us on a meandering journey through ethical and philosophical issues surrounding genome editing.

Early on, he addresses the notion of genetic determinism, which he terms the 'myth of selfhood as genome'. This is the idea that your DNA defines who you are as a person, and partly stems from historical narrative surrounding allograft rejection. Through the study of skin transplant and rejection, it is clear that individual immune systems are unique, and as we know are partially determined by genes. And so your genes define your unique immune system which in turn determines your individuality.

Dr Ball points out issues with this theory, firstly explaining the 'acquired' nature of immune tolerance during embryonic development, given the readiness with which early-stage embryos accept grafting. This suggests that one's DNA, already present from time of conception, does not in itself confer individuality of self. In discussing chimerism, present both in nature and in the lab, he further refutes genetic determinism of self as one cannot have two selves.

With this, the one thing I really struggled with, was the initial premise itself, of defining self using the immune system. Most would not view fingerprints or retinal patterns as defining features of selfhood so why should the immune system be different? Perhaps this dichotomy is due to the perceived 'invisibility' of the immune system, shrouding it in mystery and feeding a desire for self to transcend physicality. But key to this discussion, really, is further discourse on what selfhood truly means.

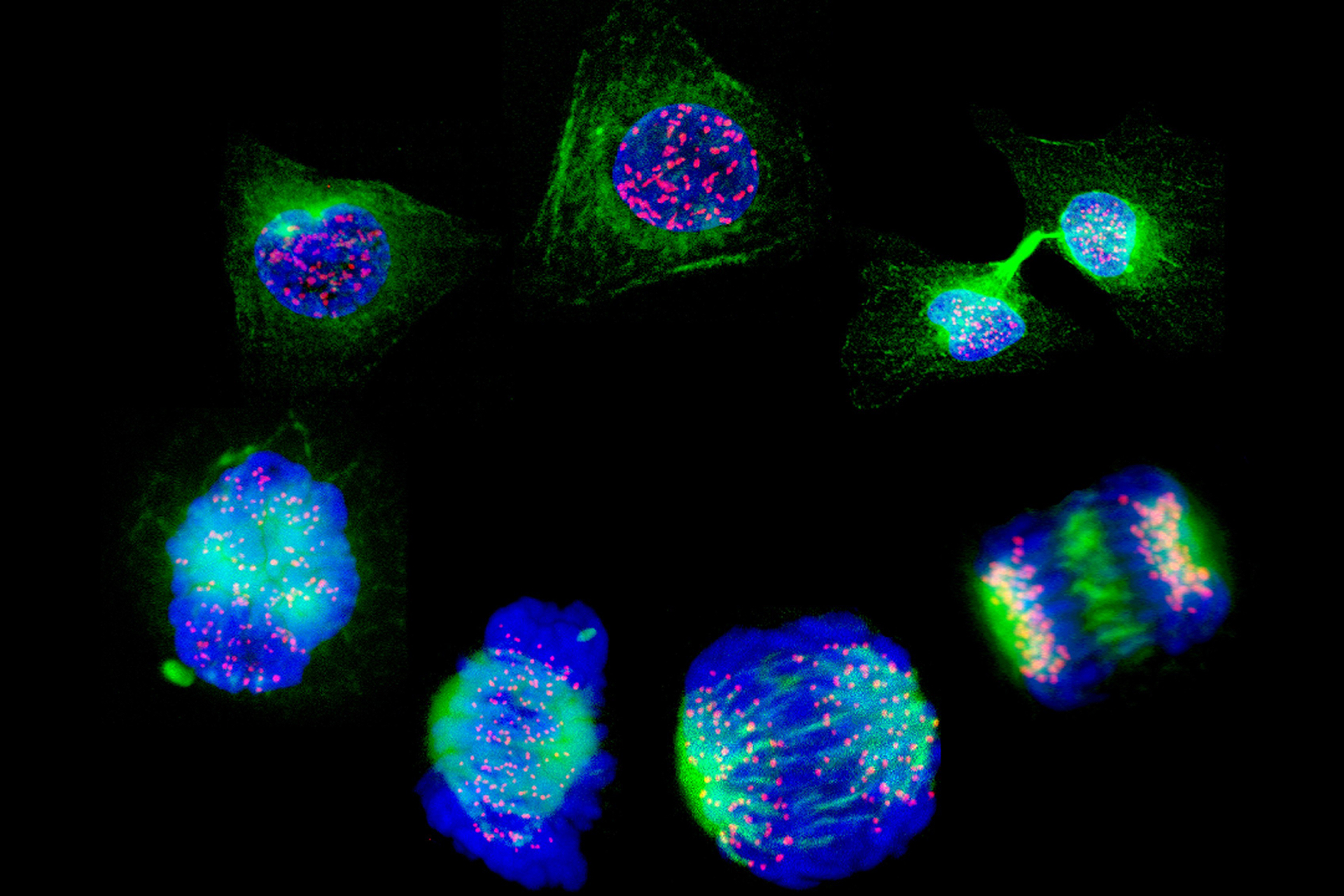

Dr Ball clearly recognises this, repeatedly returning to this theme of defining selfhood throughout the lecture. He discusses organoid formation from induced pluripotent stem cells, highlighting their potential as lab models, while questioning their moral and ontological status, particularly with brain organoids. As previously reported here, these organoids can be taught to play videogames (see BioNews 1163) and solve mathematical equations (see BioNews 1183). When then, if ever, could they be considered sentient or to have a sense of 'self'?

In the same vein, he discusses other ethical issues facing advances in genome editing, including stem-cell-based embryo models (see BioNews 1089) and pre-implantation genetic selection using polygenic risk scores, all the while returning to the question of how we view selfhood and humanity.

He also ventures into the realm of the theoretical. If a body is grown without a brain, can it have a sense of self, and if not, could we harvest its organs? Conversely, if a brain or consciousness existed without a body, would that still be human? With no way of empirically defining humanity, is believing it to be so tantamount to a religious act of faith?

You may have noticed my repeated references to the multitude of questions posed throughout the lecture. Dr Ball does this skilfully, expertly contextualising developments in genome editing in terms of their historical, theological and social relationships. But he rarely reveals personal opinion, nor does he attempt to propose any structure with which we can begin to dissect these fundamental questions.

Initially, the absence of his personal view felt disappointing and confusing. On reflection, however, that was a tad naïve to expect and if I'm being honest, lazy too. I want answers as I have none myself and am unclear where to start. His deceptively simple questions require infinitely complex answers and with only an hour allotted, I cannot fault him for not attempting them, although I reserve the right to wish he had, if just to assuage my curiosity.

Also, perhaps leaving things open was the whole point. As Dr Ball said, his aim was to 'stimulate discussion' on advances in genome editing, such that they can be used 'wisely, humanely and for the greatest benefit of all'. And what better way to start these discussions than to pose multiple fascinating unanswered questions.

With this in mind, I plan to accost friends and colleagues over the next few weeks, springing existential crises on them with their morning coffees and after-work drinks in order to help me understand what it means to be human. I suspect that bribery with cake and drinks may be required to elicit engagement. Hopefully enthusiasm and openness will make up for our lack of philosophical training. But even if it doesn't, at least there'll be cake and conversation to look forward to.

Wrapping up, this lecture gives a great overview of the historical and current ethical lens through which to consider human genome editing. I would certainly recommend watching it, particularly if you enjoy the mild anxiety of existential uncertainty and navigating an ever-expanding pool of unanswered questions on the meaning of self and humanity. For the best viewer experience however, share the chaos with like-minded friends and enjoy the ride, perhaps armed with your beverage of choice.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.